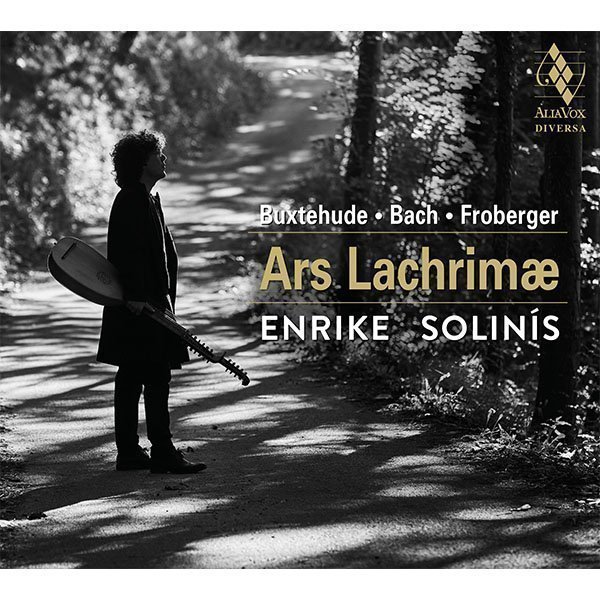

ARS LACHRIMÆ

Buxtehude · Bach · Froberguer

Alia Vox Diversa

17,99€

The title of this programme, Ars Lachrimæ, takes as its principal reference John Dowland’s masterly and inspired pavan. In aesthetic terms, it is a profoundly original meditation on musical emotions as a reflection and paradox of human existence.

ALIA VOX DIVERSA

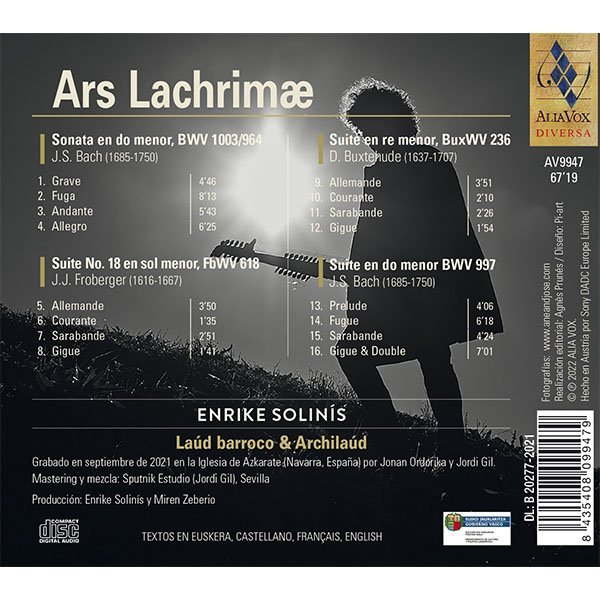

AV9947

67’19

Ars Lachrimæ

Sonata en do menor, BWV 1003/964 – J.S. Bach (1685-1750)

1. Grave 4’46

2. Fuga 8’13

3. Andante 5’43

4. Allegro 6’25

Suite No. 18 en sol menor, FbWV 618 – J.J. Froberger (1616-1667)

5. Allemande 3’50

6. Courante 1’35

7. Sarabande 2’51

8. Gigue 1’41

Suite en re menor, BuxWV 236 – D. Buxtehude (1637-1707)

9. Allemande 3’51

10. Courante 2’10

11. Sarabande 2’26

12. Gigue 1’54

Suite en do menor, BWV 997 – J.S. Bach (1685-1750)

13. Prelude 4’06

14. Fugue 6’18

15. Sarabande 4’24

16. Gigue & Double 7’01

Enrike Solinís

Laúd barroco & Archilaúd

Grabado en septiembre de 2021 en la Iglesia de Azkarate (Navarra, España)

por Jonan Ordorika y Jordi Gil.

Mastering y mezcla: Sputnik Estudio (Jordi Gil), Sevilla

Producción: Enrike Solinís y Miren Zeberio

TEXTOS EN EUSKERA, CASTELLANO, FRANÇAIS, ENGLISH

_

ARS LACHRIMÆ

The title of this programme, Ars Lachrimæ, takes as its principal reference John Dowland’s masterly and inspired pavan. In aesthetic terms, it is a profoundly original meditation on musical emotions as a reflection and paradox of human existence. The piece is a paradigm of how the rich musical tradition of the Renaissance poured its final musical inspiration into the lute and of how composers such as the English John Dowland endowed the instrument with a basic idiom and distinctive musical character. Although not expert lute players, later composers succeeded in harnessing this character as a catalyst for their own creativity: an intimate, gentle and melancholy pathos that can be traced back to the instrument’s arrival in southern Europe with the Arab musicians of the Iberian peninsula.

ENRIKE SOLINÍS

Translated by Jacqueline Minett

+ informazioni nel libretto del CD

Critici

”

Unter Solinís Fingern auf Erzlaute und Barocklaute bekommt die musizierende Haltung der Innenschau und des Nachdenklichen in diesem Repertoire großes Gewicht. Seine stille Eleganz und Mühelosigkeit der Darbietung ist dabei getragen von einer atemberaubenden technischen Präzision. Man höre allein, wie gestochen scharf er die Triller setzt, bei gleichzeitig samtweichem Verklingen. Und so ist man beglückt, dem baskischen Lautenisten eine Stunde der süßen Schwermut lang einfach nur lauschen zu dürfen.

RONDO rondomagazin.de

”

Enrike Solinís: “Hay que ser esclavo de la música, no de la partitura."

SCHERZO - Disco EscepcionalEduardo Torrico - Manuel de Lara Ruiz

”

"Ars Lachrimae", l'últim disc del virtuós instrumentista de corda polsada Enrike Solinís. Editat per Alia Vox, el disc està integrat per obres de Johann Sebastian Bach, Johann Jakob Froberger i Dietrich Buxtehude. Enrike Solinís sempre s'ha sentit atret per la música de diferents cultures, regions i èpoques, i ha reflectit aquesta diversitat en la seva personalitat musical, que juntament amb la seva capacitat tècnica i expressiva fa que molts el considerin un dels principals.

Catalunya Ràdio, 10/03/22

”

Enrike Solinís “Es más moderno escuchar música antigua que reguetón.”

Maite Redondo. DEIA, 15.4.22

Compartir