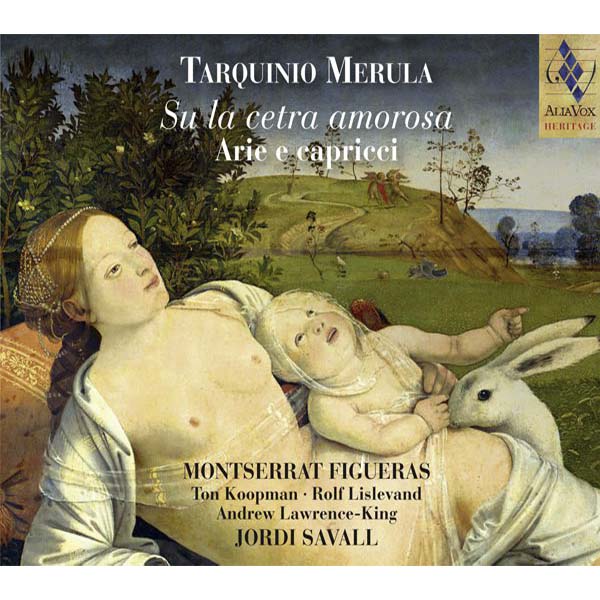

TARQUINIO MERULA

Su la cetra amorosa

Hespèrion XXI, Jordi Savall, Montserrat Figueras

15,99€

Reference: AVSA9862

- Jordi Savall

- Montserrat Figueras

Along with Luigi Rossi, Francesco Cavalli and Giacomo Carissimi, Tarquinio Merula belongs to that generation of composers, born between 1595 and 1605, for whom the concertante style was no longer a novel type of idiom, but the musical medium they had been familiar with from childhood as the prevailing musical language of the time. Tarquinio Merula was born in Busseto in 1595 and probably received his musical training at Cremona cathedral. He was appointed organist at Lodi (in Lombardy) and then at the court of the King of Poland in Warsaw and, from 1626 onwards, he switched several times from the post of maestro di cappella at Cremona cathedral to the same post at Bergamo, and vice versa.

Whilst Rossi, Cavalli and Carissimi did not reach the height of their careers until the middle of the century or later, the major part of Merula’s works was published at a time when musical life in Italy was still dominated by the outstanding composers of the previous generation, Claudio Monteverdi and Alessandro Grandi. Moreover, he was Grandi’s successor at Bergamo on the latter’s death.

+ information in the CD booklet

JOACHIM STEINHEUER

Translated by Mary Pardoe

Share