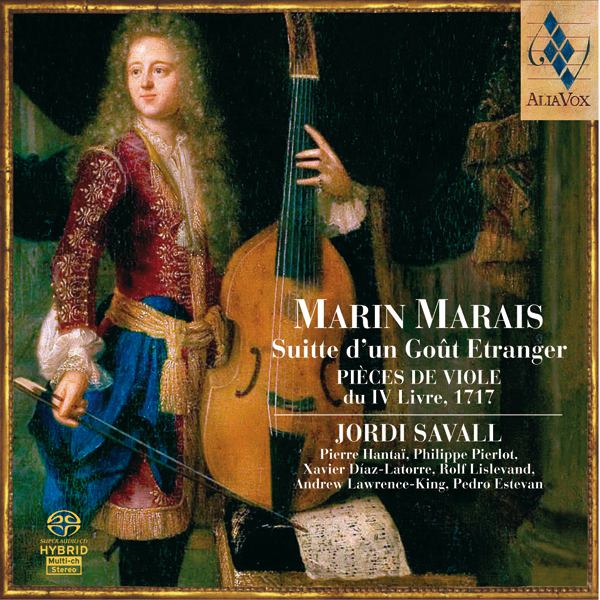

MARIN MARAIS

Suitte d’un Gôut Etranger, Pièces de Viole IV Livre

Jordi Savall

17,99€

Ref: AVSA9851

- Jordi Savall

- Pierre Hantaï

- Philippe Pierlot

- Xavier Díaz-Latorre

- Rolf Lislevand

- Andrew Lawrence-King

- Pedro Estevan

It was around 1959 that I discovered the existence of Marin Marais and his Pieces for Viol. I was seventeen and had been studying the cello for just over two years. Being very inquisitive by nature, I was already searching for unknown works, music that nobody played any more. At number 97 on the famous “Ramblas” in Barcelona, in the music shop called “CASA BEETHOVEN”, I was intrigued to find a “Suite in D minor”, arranged for the cello by Christian Döbereiner and published by SCHOTT & Co. in 1933. I remember being instantly charmed by the highly original character of the various pieces it contained: Prélude, Sarabande Grave, Paysanne, Charivary and, in particular, by the Variations of the Folies d’Espagne. What fascinated me about all those pieces that I gradually explored and continued to revisit, like those by François Couperin, Caix d’Hervelois, August Kühnel, Jan Schenk, Christopher Simpson, Diego Ortiz and, of course, J.S. Bach’s three sonatas for viola da gamba and harpsichord, was their distinctive style, one which although belonging to an earlier, unfamiliar age, was at the same time acutely relevant because of its vitality, poetry and imagination.

A few years later, during the summer of 1965, just one month after completing my cello studies, I returned to Barcelona after a musical study trip to Santiago de Compostela where I had been working on Baroque chamber music with the harpsichordist Rafael Puyana. He advised me to learn to play the viola da gamba, the instrument for which the music that I played on the cello had originally been composed. On my journey back to Barcelona, I made the following entry in my diary “Find a viola da gamba!” On my arrival, there was a great surprise waiting for me: Enric Gispert, the director of the early music ensemble ARS MUSICAE, wanted to talk to me. He offered to lend me a viola da gamba, if I was serious about learning the instrument. He invited me to collaborate with him, helping to put together a viol ensemble and to take part in concerts and recordings. I later found out that it was Montserrat Figueras, who sang with the ensemble and also studied the cello at the Barcelona Conservatoire, who had brought to Enric Gispert’s attention that young cellist who played Bach and the Baroque repertoire tolerably well. Another decisive encounter which was to play, as it still plays today, an essential and indissoluble part in every creative aspect of both my personal and my musical life.

+ information in the CD booklet

JORDI SAVALL

Bellaterra, summer 2006

(1) Selections devoted to Marais’s other books were recorded – also at Saint Lambert des Bois – in April 1978 (First Book), March 1983 (Fifth Book) and January 1992 (Third Book).

(2) Quoted in Vie de musiciens et autres joueurs d’instruments du règne de Louis le Grand.

© Alia Vox. Translated by Jacqueline Minett

Share