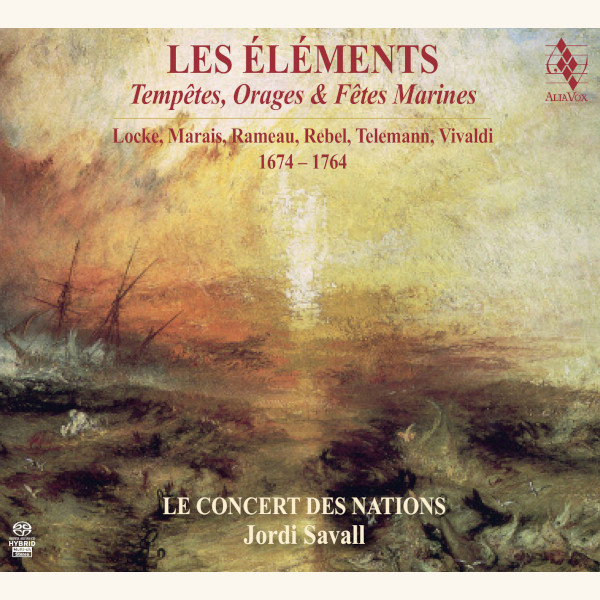

LES ÉLÉMENTS

Tempêtes, Orages & Fêtes Marines

1674 – 1764

Jordi Savall, Le Concert des Nations

17,99€

Reference: AVSA9914

- Le Concert des Nations

- Direcció: Jordi Savall

During the 18th century, European and, in particular, French musicians forged a speciality in the art of tone painting. Jean-Féry Rebel set out his intentions in his Foreword to the The Elements, writing: “the Air is ‘depicted’ by sustained notes followed by candenzas played on piccolos.” In this live recording of a concert performed at the Fontfroide Festival, our “musical painters” – Matthew Locke, Marin Marais, Georg Philipp Telemann, Antonio Vivaldi, Jean-Philippe Rameau and Jean-Féry Rebel – speak for themselves.

During the 18th century, European and, in particular, French musicians forged a speciality in the art of tone painting. Jean-Féry Rebel set out his intentions in his Foreword to the The Elements, writing: “the Air is ‘depicted’ by sustained notes followed by candenzas played on piccolos.” In this live recording of a concert performed at the Fontfroide Festival, our “musical painters” – Matthew Locke, Marin Marais, Georg Philipp Telemann, Antonio Vivaldi, Jean-Philippe Rameau and Jean-Féry Rebel – speak for themselves.

We symbolically begin the first part of this recording (CD1), with the extraordinary and striking “representation of chaos,” which Rebel included in his ballet The Elements in 1737. The first part of this descriptive and symbolic programme will be followed by incidental music composed by Matthew Locke for the play The Tempest, and concludes with one of the most famous, Antonio Vivaldi’s La Tempesta di mare (The Sea Tempest) in F major (RV 433, Op 10 No.1), composed for recorder and strings.

+ information in the CD booklet

JORDI SAVALL

Bellaterra, 1 October, 2015

Translated by Jacqueline Minett

Share