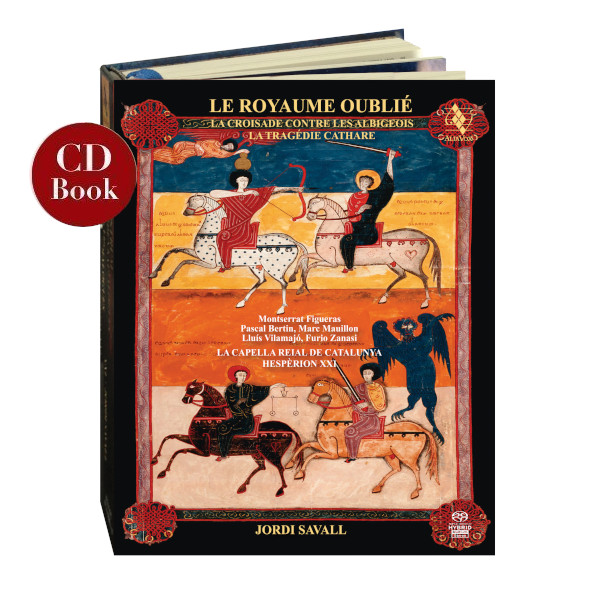

LE ROYAUME OUBLIÉ

La Tragédie Cathare

Hespèrion XXI, Jordi Savall, La Capella Reial de Catalunya

32,99€

Referència: AVSA9873

la Coisade Contre les Albigeois

- La Capela Reial de Catalunya

- Hespèrion XXI

- Jordi Savall

- Pilar Jiménez Sánchez

- Manuel Forcano

- Anne Brenon

- Martín Alvira Cabrer

- David Renaker

- Sergi Grau Torras

The Forgotten Kingdom refers, first of all, to the Cathars’ cherished “Kingdom of God” or “Kingdom of Heaven”, which is promised to all good Christians after the Second Coming of Christ; but in the present project it also recalls the forgotten kingdom of Occitania. The “Provincia Narbonensis”, a land of ancient civilisation on which the Romans made their mark, and which Dante described as “the country where the langue d’Oc is spoken”, is succinctly described in the 1994 edition of the dictionary Le Petit Robert 2 as follows: “n.f. Auxitans Provincia. One of the names given to the Languedoc in the Middle Ages.” As Manuel Forcano observes in his interesting article Occitania: Mirror of Al-Andalus and refuge of Sepharad, “From ancient times until the Middle Ages Occitania was a territory that was open to all kinds of influences and whose borders were permeable to different peoples and ideas, a fragile crucible which blended knowledge, music and poetry from learned and sophisticated Al-Andalus to the South, as well as from France and Europe to the North, and from Italy and the Balkans and the exotic world of Byzantium to the East.” All these many varied influences made it one of the most active centres of Romance culture, a country with an intense intellectual activity and a degree of tolerance that was for the medieval period. It not surprising that the udri love of the Arabs should have inspired the poetry and the fin’amor of the trobairitz and troubadours; nor is it surprising that the Cabbala should have sprung out of its Jewish communities. Similarly, it is not strange that the Christians of Occitania should have proposed and discussed different ecclesiastical models, that of the bons homes, or Catharism, and that of the Catholic clergy.

+ information in the CD booklet

JORDI SAVALL

Bellaterra, 3rd October, 2009

Translated by Jacqueline Minett

Share