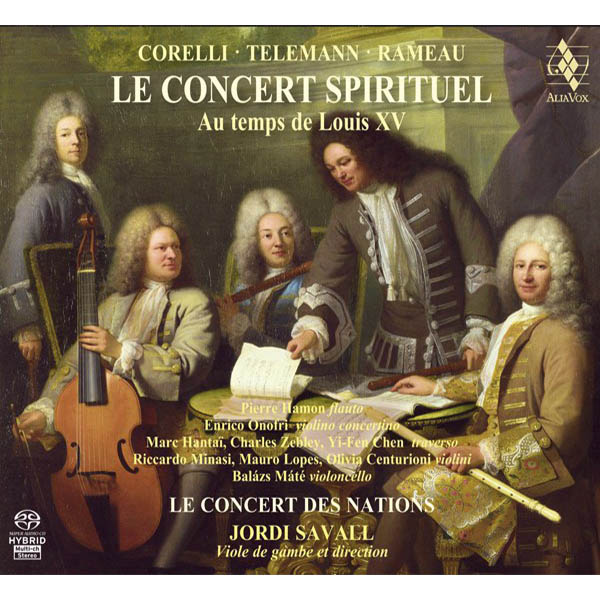

LE CONCERT SPIRITUEL

Au temps de Louis XV (1725-1774)

Jordi Savall, Le Concert des Nations

17,99€

Reference: AVSA9877

- Le Concert des Nations

- Jordi Savall

The origin of private concerts, both in France and the rest of Europe, dates back to the time when music began to spill out from churches and palaces to grace private houses and open-air gardens. According to Huber Le Blanc (the author of the famous pamphlet Défense de la Basse de viole, contre les entreprises du violon et les prétensions du violoncelle, Amsterdam 1740), in Paris at the end of the reign of Louis XIV, “nothing was so fashionable as music, the passion of the well-to-do and persons of quality”, but it was during the Regency period that the first series of fully-fledged private concerts, with the early activities of the soon to be famous Concert Spirituel cycle began. The name Concert Spirituel derives from the fact that it was created so that concerts could be performed during Lent and on other religious holidays of the Catholic Church, a total of some thirty-five days each year, during which all the “profane” activities of the principal musical and theatrical institutions such as the Paris Opera, the Comédie-Française and the Comédie-italienne, were brought to a standstill.

For many years, the concerts were held in the magnificently decorated Salle des Cent Suisses (Hall of the Hundred Swiss Guards) at the Tuileries Palace. Concerts started at six o’clock in the evening and were principally intended for the haute bourgeoisie, the minor aristocracy and foreign visitors. The programmes consisted of a mixture of sacred choral and French virtuosic instrumental works, as well as works by Italian and German composers. Anne Danican Philidor, born in Paris in 1681, the son of King Louis XIV’s music librarian, opened the series of concerts on 18th March, 1725. The programme for the first concert consisted of a suite of airs for violins from Michel-Richard Delalande’s grand motet “Confitebor”, Arcangelo Corelli’s Concerto grosso written for Christmas Eve, and a second motet à grand choeur “Cantate Domino”, also by Delalande. Although the repertoire was overwhelmingly dominated by French music in the early years, with works by Couperin, Campra, Delalande, Mondonville, Rebel, Bernier, Gilles, Boismortier, Corrette, Charpentier and Rameau, it was not long before instrumental and vocal music by Italian, English and German composers such as Corelli, Pergolesi, Vivaldi, Bononcini, Geminiani, Handel, Telemann, Haydn and Mozart was included, to the delight of all those who welcomed and revelled in the latest musical novelties.

+ information in the CD booklet

JORDI SAVALL & JOSEP MARIA VILAR

Translated by Jacqueline Minett

Share