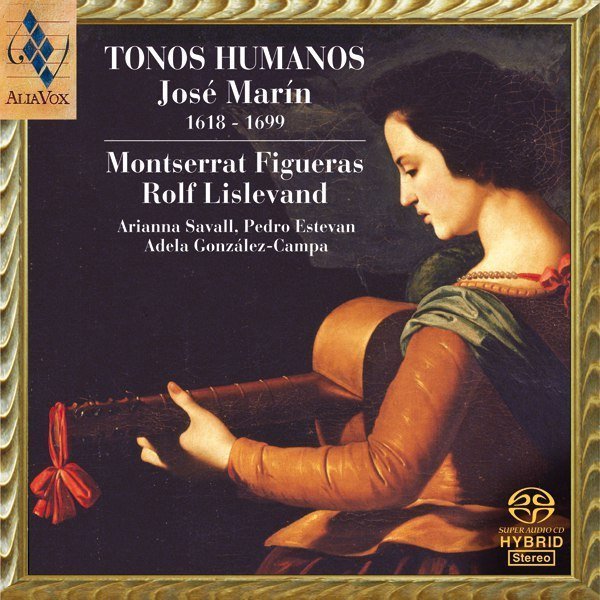

JOSÉ MARÍN

Tonos Humanos

Montserrat Figueras

17,99€

Ref: AVSA9802

- Montserrat Figueras

In the Iberian peninsula during the seventeenth century, a wide variety of dances were set to words and song, while at the same time many ballads and carols were also danced. Our outstanding literary and dramatic authors, from Juan del Enzina to Calderón de la Barca, including Miguel de Cervantes and Lope de Vega, have left us in their curtainraisers, interludes, comedies and dances a wonderful repertoire “rich in carols, folk songs, seguidillas and sarabandas”, which beckon one to dance “hasta molerse el alma” (until one is fit to drop – La Entretenida) and“cantaba con tal donaire” (“were so charmingly sung” – La Gitanilla) “que suspendían los sentidos y los ánimos de cuantos los escuchaban” (that they bewitched the soul and the senses of all who listened to them – Persiles y Segismunda). That extraordinary genius Miguel de Cervantes tells us in “La Gitanilla” that his gypsy heroine Preciosa, danced and sang to the sound of the tabor and the castanets because she was performing “por ser la danza cantada” (a song and dance) and that she accompanied herself “unas sonajas, al son de las cuales dando en redondo largas y ligerisimas vueltas cantó el romance” (on a rattle, singing her ballad as she lightly danced in wide, whirling circles”.

+ information in the CD booklet

MONTSERRAT FIGUERAS

Bellaterra, January 1998

Translated by Jacqueline Minett

Share