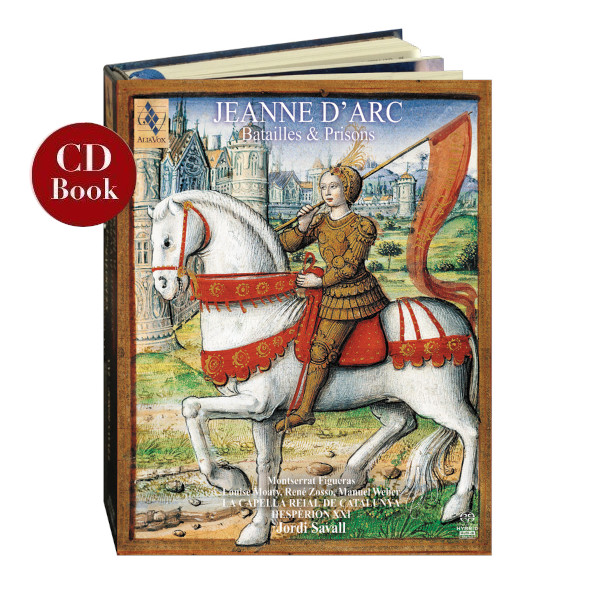

JEANNE D’ARC

Batailles et Prisons

Hespèrion XXI, Jordi Savall, La Capella Reial de Catalunya, Montserrat Figueras

32,99€

Refèrencia: AVSA9891

- Jordi Savall

- La Capella Reial de Catalunya

- Hespérion XXI

Thanks to numerous studies by eminent historians and researchers in France and elsewhere, the true story of Joan of Arc is nowadays accessible and, in general, quite well known throughout the world. It is a story which transcends the terms “myth”, “legend” and “folklore” that have so often been used in connection with her, for our knowledge about Joan the Maid is based on scrupulously authentic documents: chronicles, public and private letters, records of the Parliament in Paris, manuscripts signed by notaries, and the transcripts of the two trials she endured, one while she was alive and the other after her death, all of which have been meticulously sifted through using the most rigorous historical methods. Unfortunately, this has not prevented all manner of legends and false historical accounts being presented as hidden truths or even new discoveries. However, what has astonished me most during the preparation of this project is how easily even cultured people can overlook essential information, such as the signing of the Treaty of Troyes, which underlies the very origin and culmination of this long and ancient conflict in which the English and the French were violently pitted against each other. “Without the senses there is no memory, and without memory there is no intelligence,” recalls Voltaire in his Aventure de la mémoire (1773). That is why, important though it is, our individual memory often hinges on the facts, knowledge and experiences that are dear and close to us, or that have made a deep impression on us. The sum total of all these memories shapes the historical memory of a people, which in turn determines our ability to keep alive not only the memory of heroic and extraordinary feats accomplished by men and women of the past, but also the tragedy and suffering of individuals who have struggled – often alone, as in the case of the Maid of Orleans – against stifling ideologies and lethal fanaticism. Absolute evil is always the evil that man inflicts on his fellow man. Although we say nothing here that has not been said and repeated before, we echo the words of Régine Pernoud, who writes: “the past offers no example of a destiny more extra-ordinary than that of this nineteen-year-old “Maid”. Whether one regards her as an emissary from God or a heroine with a mission to liberate her people, nobody remains indifferent to her: from Voltaire to Schiller, from Anatole France and Renan to Péguy and Claudel, from Chartists to amateur historians, from Japanese scholars to Russian academics… all have been fascinated by her.”

+ information in the CD booklet

JORDI SAVALL

San Juan de Puerto Rico

4th March, 2012

Translated by Jacqueline Minett

Share