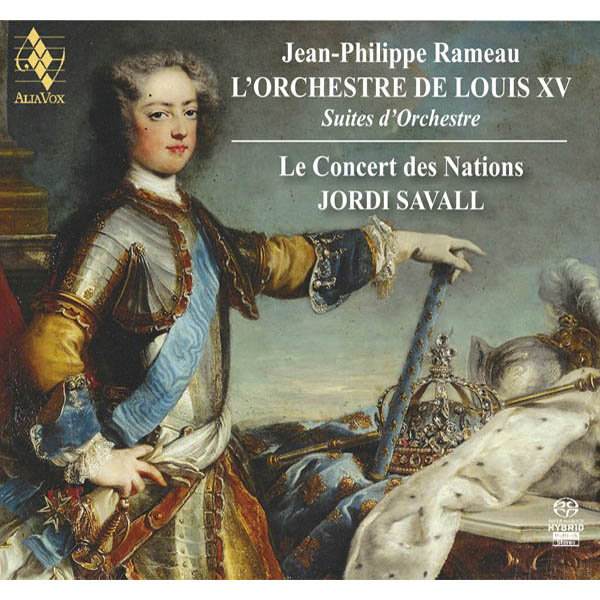

JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU

L’Orchestre de Louies XV

Jordi Savall, Le Concert des Nations

17,99€

Referència: AVSA9882

- Jordi Savall

- Le Concert des Nations

The preparation and realisation of this project were carried out in the context of our “First Professional, Research and Performance Using Period Instruments Academy.” Organised by CIMA (International Early Music Centre) Foundation and ESMUC, under my own direction, with the collaboration of Manfredo Kraemer and the soloists of Concert des Nations, the Academy’s objective was to foster the participation of young professional musicians from various countries in Europe and America. Our master classes on individual and ensemble playing, sound, articulation, ornamentation, improvisation, phrasing, dynamics and characteristics of dance and tempo in the performance of orchestral music at the time of Rameau informed and enhanced the rehearsals leading up to concerts in Barcelona, Eindhoven, Cologne, Rotterdam, Metz, Paris and Versailles. The present recording was made in the wonderful concert hall of the Arsenal in Metz, followed a few days later by the DVD recording of the concert given at the Théâtre Royal de Versailles.

“A good musician must abandon himself to all

the characters he sets out to depict…but

the music must speak to the soul.”

Jean-Philippe Rameau

The recording

This recording devoted to Jean-Philippe Rameau and the orchestra of Louis XV follows our previous releases that focussed on the orchestras of Louis XIII and Philidor, and Louis XIV and Lully. Although Rameau’s relationship to Louis XV and his role under the king cannot be compared to those enjoyed by Lully under Louis XIV, if the living memory of the orchestra of King Louis XV of France were to be linked to one musician above all others, that musician would undoubtedly be Jean-Philippe Rameau. Indeed, the extraordinary diversity, richness and inventiveness of the orchestral language, forms and instrumentation that are Rameau’s legacy, particularly in his overtures, symphonies, dances and other “airs à jouer” included in his more than 17 operas, ballets, tragedies and pastorales, justify his being regarded as the most important, innovative and brilliant French composer of his age, especially with regard to orchestral music and opera. Once we had overcome the initial quandary of choosing the pieces, our present selection of four “instrumental suites or symphonies” was taken from four of Rameau’s most important works for the stage: the ballet héroïque, Les Indes Galantes (1735), the pastorale héroïque, Naïs (1748) and the two lyric tragedies Zoroastre (1749) and his last production, Les Boréades (1764). Rameau intimately blends the orchestra with the vocal music to form his scenic ensembles, as well as incorporating all the dances that were so popular with the public during the first half of the 18th century. In the opéra-ballet, as in the pastorale and the lyric tragedy, dance performed a dual function: on the one hand, it could provide an “embellishment” to the scenography of the work, having no direct connection with the action; on the other hand, it could be a dramatic means of moving the action forward or highlighting important moments in the plot.

+ information in the CD booklet

JORDI SAVALL

Bellaterra, April 2011

Translated by Jacqueline Minett

Share