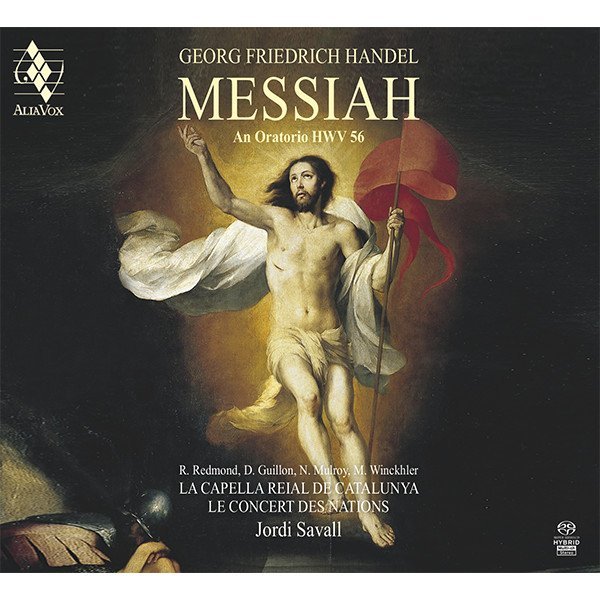

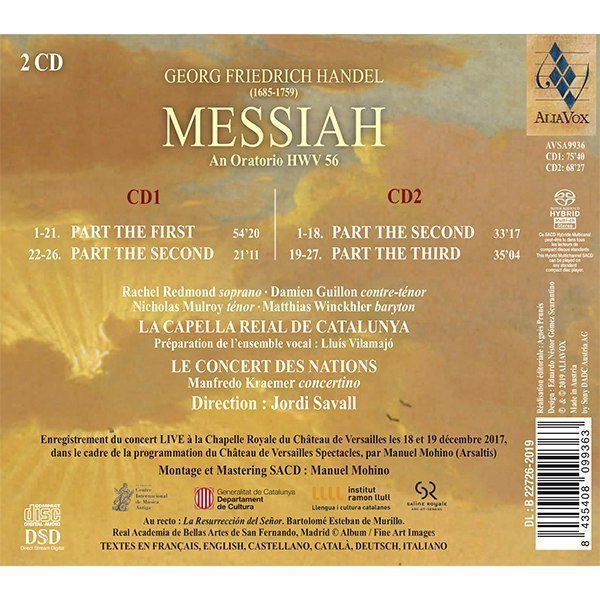

GEORG FRIEDRICH HANDEL

Messiah

Jordi Savall, La Capella Reial de Catalunya, Le Concert des Nations

29,99€

All the wonderfully diverse features of Baroque expression and vocal and instrumental declamation are present in Handel’s Messiah. It is a sublime musical meditation which transcends simple narrative, going beyond the reality of Jesus to the mystery of Creation itself and Redemption in a three-fold reflection on the struggle between Light and Darkness, the redemption of Humanity, and the relationship between God and Man.

GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL

Searching for the Light

MESSIAH

To fully appreciate what Messiah meant to Handel himself, we must consider the spiritual, financial and physical crisis that he experienced in 1737; during that year the principal opera houses such as the Haymarket and the Nobility Opera went bankrupt. On 13th April, Handel was stricken with an attack of paralysis and on 20th November Queen Caroline, his most constant patron and loyal friend, passed away. Added to this, he had been under the terrible, relentless pressure of his dual responsibilities as a musician and impresario throughout 1736. Moreover, it is no wonder that his prodigious workload during 1737 took its toll on his robust constitution: beginning in January his creative energies produced Partenope, Arminio, Il Parnassso in Festa, Alexander’s Feast, Il Trionfo and Esther, in which -to the rapture of his audiences- he also performed the Organ Concertos, which had become one of the mainstays of his popularity. No sooner had he finished Berenice, Handel arranged a new pasticcio: Didone abbandonata. However, on this occasion he was unable personally to see the production through, because on 13th April he was afflicted with a paralysis of his right side, which also affected his intellectual faculties. Yesterday’s “Colossus” was suddenly a pitiable, prostrate figure. On 14th May, the London Evening Post reported on the composer’s ill health “which, if he don’t regain, the publick will be depriv’d of his fine Compositions.” In a gesture of support for the musician, the Royal Family nevertheless attended the premiere of Berenice on 18th May. Without Handel at the helm, however, the enterprise was in jeopardy. One last composer’s benefit performance was given on 15th June. A few days later, the troupe broke up and Strada and Conti left London. On 11th June the Nobility Opera also closed its doors.

+ information in the CD booklet

JORDI SAVALL

Bellaterra, 11th September, 2019

Translated by Jacqueline Minett

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gallois, Jean. Haendel. Éditions Solfèges/Seuil. Paris 1980.

Labie Jean-François. G. F. Haendel. Diapason. Éditions Robert Laffont. Paris 1981.

Mainwaring, John, Memoirs of the Life of the Late George Frederic Haendel, R. & J. Dodsley, London 1760.

Müller von asow, Hedwig, and Müller, Erich H., Georg Friedrich Händel: Biographie, Briefe und Schriften, Lindau im Bodensee: Frisch und Perneder, 1949.

Raugel, Félix. Georges Frédéric Haendel. Histoire de la Musique, Encyclopédie de La Pléiade. Volume I). Éditions Gallimard. Paris 1960. Pp. 1863-1881.

Rouviere Olivier. Le Messie de Haendel. Programme notes. Concerts at Chapelle Royale, Versailles, 18/19 December 2017.

Critics

”

”a sublimely passionate and compassionate performance"

Mark Swed, Los Angeles Times

”

”Do we need yet another Handel Messiah? It is, hands down, the most popular Christmas oratorio of all time. Well, listen to Jordi Savall’s revelatory version and you can’t help but agree that there is room for one more. Yes, indeed. Savall, the viola da gamba–playing rock star of early music, has brought an astounding amount of beauty to this very familiar piece. “ “Savall and his musicians here provide a leaner, cleaner, and revelatory Messiah — both uplifting and thrilling."

ArtsFuse

”

”Jordi Savall lo affronta come una «sublime meditazione musicale»"

Avvenire

Share