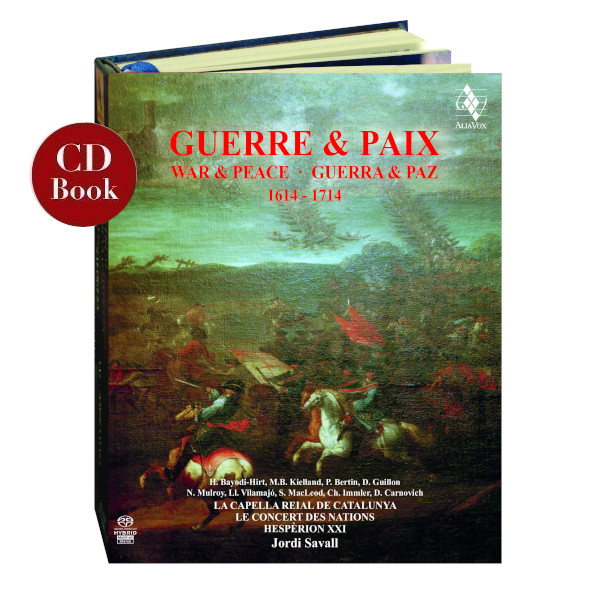

GUERRE & PAIX

(1614-1714)

Hespèrion XXI, Jordi Savall, La Capella Reial de Catalunya, Le Concert des Nations

31,36€

Reference: AVSA9908

- Jordi Savall

- la Capella Reial de Catalunya

- Le Concert des Nations

- Hespèrion XXI

In this new CD-Book War & Peace in Europe in the Age of the Baroque, we evoke through music the great century which preceded the end of the War of the Spanish Succession in 1714: a rich musical fresco and an in-depth historical review of a very brief but highly representative period in the history of Europe and its conflicts. From the Ottomans’ attack on Hungary in 1613, the Massacre of the Jews in Frankfurt in 1614 and the beginning of the Thirty Years War, to the Peace Treaty of Utrecht and the fall of Barcelona, we can see the extent of this unremitting tragedy of European civilization: the widespread use of the “culture of war” as the principal means of settling cultural, religious, political and territorial differences. This inventory of the long, sad succession of confrontations, wars, invasions, attacks, massacres, aggressions, sacking and fighting between peoples and ethnic groups throughout the history of mankind (in this case in Europe), teaches us that it is both necessary and urgent to acquire new ways of relating to each another if we are to reconcile differences in a world that is fertile in action, word and thought.

Un segle en guerra, 1614-1714

“[…] there is greater glory in

killing war itself with words

than by killing men with swords;

and by achieving or maintaining peace through peace

rather than through war.”

Augustine (354-430)

Letter to Darius, 229, 2

In this new CD-Book War & Peace in Europe in the Age of the Baroque, we evoke through music the great century which preceded the end of the War of the Spanish Succession in 1714: a rich musical fresco and an in-depth historical review of a very brief but highly representative period in the history of Europe and its conflicts. From the Ottomans’ attack on Hungary in 1613, the Massacre of the Jews in Frankfurt in 1614 and the beginning of the Thirty Years War, to the Peace Treaty of Utrecht and the fall of Barcelona, we can see the extent of this unremitting tragedy of European civilization: the widespread use of the “culture of war” as the principal means of settling cultural, religious, political and territorial differences. This inventory of the long, sad succession of confrontations, wars, invasions, attacks, massacres, aggressions, sacking and fighting between peoples and ethnic groups throughout the history of mankind (in this case in Europe), teaches us that it is both necessary and urgent to acquire new ways of relating to each another if we are to reconcile differences in a world that is fertile in action, word and thought.

+ information in the CD booklet

JORDI SAVALL

Bellaterra, Autumn 2014

Translated by Jacqueline Minett

Share