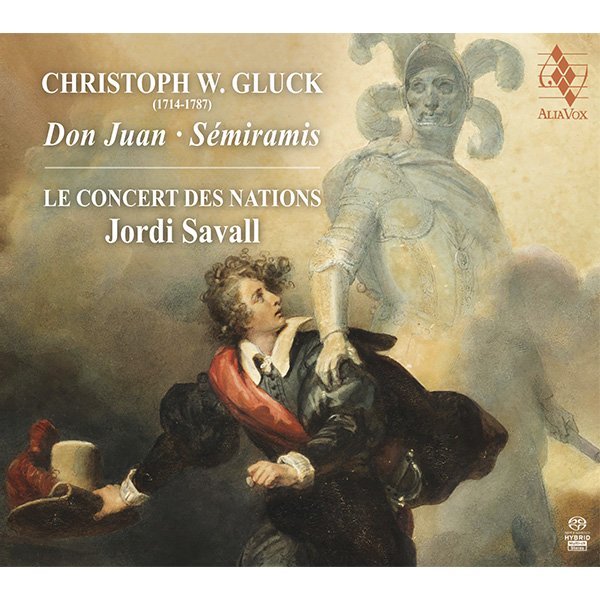

CHRISTOPH W. GLUCK

Don Juan · Sémiramis

Jordi Savall, Le Concert des Nations

17,99€

In 1761, a year before his masterpiece Orpheus and Eurydice, Gluck was already largely renewing another musical genre, the ballet, in his adaptation of a work by Molière for Viennese audiences: Don Juan. A year later, this would be followed by another, Semiramis. These two works are innovative in that they offer for the first time a coherent narrative in which all the resources of the orchestra are placed at the service of expressiveness. Jordi Savall and Le Concert des Nations recover all the nuances of these scores, reminding us that, a quarter of a century before Mozart, the stages of Europe were being regaled with all the evocative power of music by another outstanding figure: C. W. Gluck.

ALIA VOX

AVSA9949

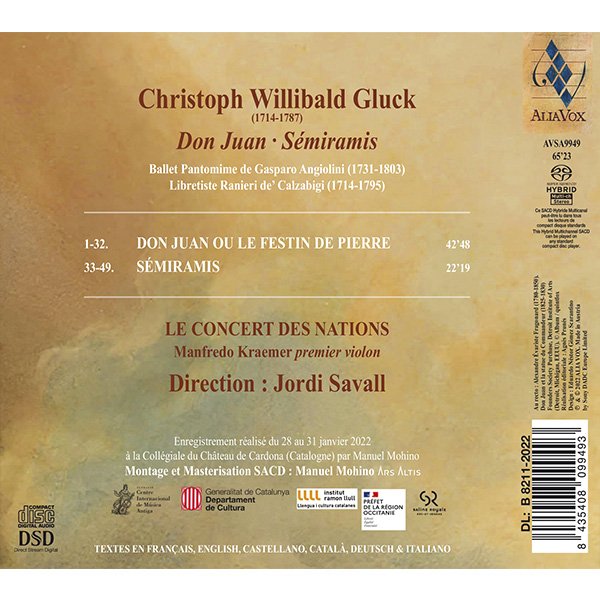

CHRISTOPH W. GLUCK

(1714-1787)

Don Juan · Sémiramis

Pantomime ballet by Gasparo Angiolini (1731-1803)

Librettist Ranieri de’ Calzabigi (1714-1795)

1-32. DON JUAN OU LE FESTIN DE PIERRE 42’48

33-49. SÉMIRAMIS 22’19

LE CONCERT DES NATIONS

Manfredo Kraemer premier violon

Direction : Jordi Savall

Recording made from 28 to 31 January 2022

at the Collegiate Church of Cardona Castle (Catalonia) by Manuel Mohino

Editing and SACD mastering: Manuel Mohino ARS ALTIS

_

Stage dance as an experiment:

Gluck’s Viennese ballet music for Don Juan and Sémiramis

The second half of the 18th century is one of the most remarkable periods in the history of music in terms of change and innovation, the broadening of existing forms, genres and styles and the search for new possibilities of expression. The American musicologist Daniel Heartz rightly considers this phase, which emerged against the cultural backdrop of the European Enlightenment, to be “critical years in European Musical History”. This is especially true of musical theatre: almost simultaneously, bold experiments in opera and stage dance occurred in various cultural centres in Europe, including Vienna. In the case of the Austrian capital, it was Christoph Willibald Gluck who, together with his collaborators Ranieri de’ Calzabigi and Gasparo Angiolini, tried out new ways of fusing music and drama in opera and dance.

After a number of successful years as a composer of operas in Italy, Gluck joined Pietro Mingotti’s opera company as music director before finally settling in Vienna in 1750. In Italy he had earned a reputation as a talented musician as promising as he was idiosyncratic: he was already considered “a young man of outstanding ability and fiery temperament” (Saverio Mattei, 1756), and even then his rather unconventional musical style gave rise to controversy, as in 1752 at Naples, when the bold harmonic progressions and expressive dissonances of the famous aria “Se mai senti spirarti sul volto” from his opera La clemenza di Tito were criticised by some as a violation of the rules of music theory, whilst praised by others as forward-looking stylistic innovations.

+ information in the CD booklet

IRENE BRANDENBURG

Paris Lodron University Salzburg

Translation: Jacqueline Minett

Critics

”

"Jordi Savall presenta un nou àlbum dedicat a la música de Christoph Willibald Gluck.Un àlbum doble del segell Alia Vox que conté l'enregistrament de dos ballets pantomimes: "Don Joan" i "Semíramis", que interpreta Le Concert des Nations, dirigits per Jordi Savall. Aquest disc es va enregistrar del 28 al 31 de gener d'aquest 2022, a la col·legiata del castell de Cardona. "

CATALUNYA RADIO 14.09.2022

”

"Avec le Concert des Nations, le chef espagnol fait vivre l’action de ce Don Juan comme si c’était une histoire racontée en images musicales, que l’on peut suivre avec précision grâce au texte inséré dans le livret (en six langues !), donnant ainsi la possibilité au mélomane de se créer son propre théâtre intérieur. Il y a chez Savall un savant mélange d’action chorégraphique et de portée métaphysique, avec une sensualité parfois teintée d’ironie qui se traduit par des traits dynamiques, un relief nerveux et une vitalité débordante. A tel point que l’on arrive à la Danse des Furies tout étonné d’être déjà au dénouement du châtiment. L’orchestre énergique, tout en nuances et en suggestions, est mené avec un allant (les cors, les tempêtes de cordes) qui emporte l’adhésion. "

CRESCENDO MAGAZINE. Jean Lacroix. 16 septembre 2022

”

"Dans cette proposition discographique, l’engagement et l’énergie font foi, donnant vie à un spectacle de scène grâce à l’expressivité des instrumentistes et des quelques annotations dans le livret d’accompagnement, qui permettent à l’auditeur d’associer l’intrigue à la musique qu’il entend. "

ResMusica. Charlotte Saulneron. 29 septembre 2022

”

"Jordi Savall sabe exprimir el carácter en cada movimiento, como si de personajes de una ópera se tratase, cosa que nos permite captar cuando la música es agresiva, dulce, alegre, enfadada y una inmensidad de adjetivos más. "

Àngel Villagrasa Pérez. Melómano digital. 14/11/22

”

We stay in the 18th century for the latest release from Jordi Savall and the merry musicians of Le Concert des Nations. Two attractive and ingenious “ballet pantomimes” by Gluck reflect ballet music in transition, moving from the dance divertissement to music following a narrative line.""Listening to the highly charged Semiramis is like absorbing a film soundtrack with eyes closed. Action and characterisations matter less in Don Juan, though there’s no doubting where the hero ends up, tossed into hellfire by demons. The playing throughout is exemplary, delightfully colourful and driven along with a natural bounce. Albums like this may not change the world, but they definitely make life worth living. "

Jordi Savall - Gluck (****)THE TIMES. Geoff Brown - July 06 2022

”

"Jordi Savall en gluckiste irrésistible : Les ballets fantastiques d’Angiolini, la musique frénétique et psychologique de Gluck"

Le Clic - Classiquenews.com – juin 2022

Share