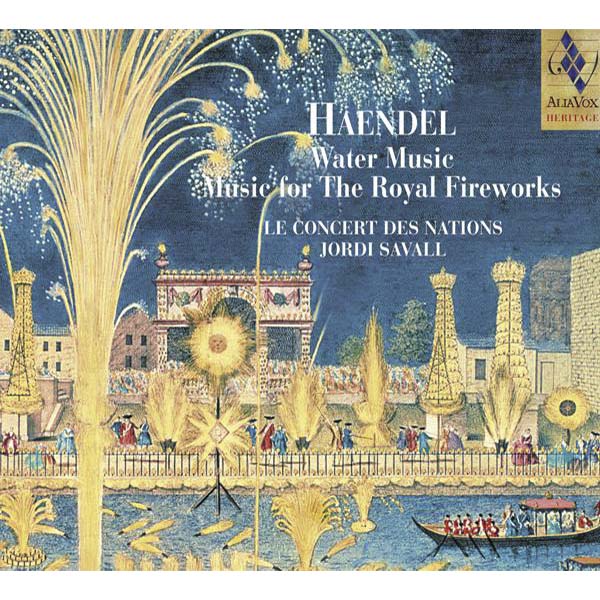

G.F. HAENDEL

Water Music

Music for The Royal Fireworks

Jordi Savall, Le Concert des Nations

15,99€

Reference: AVSA9860

-

- Jordi Savall

- Le Concert des Nations

On 25th September 1714, just six days after landing at Greenwich, a Te Deum by Handel was given in the king’s presence and the same year he also attended a performance of Handel’s opera Rinaldo. If Handel was in disgrace, his music was not. And the only royal excursion on the river with music by Handel that we know of did not take place until 17th July 1717. There are three contemporary accounts of this event. The first two appeared in English newspapers. The Political State of Great Britain of 1717 reports that, on the evening of Wednesday 17th July, the king sailed to Chelsea “with excellent Musick organized by Baron Kilmanseck for his entertainment”; at three o’clock in the morning, he sailed back to Whitehall, and from there went on to St James’s palace. The Daily Courant for 19th July speaks of “the Musick, in which fifty instruments of all kinds played, throughout the journey from Lambeth the most agreeable symphonies composed especially for the occasion by Mr Handel. They pleased His Majesty so much that they were played three times, going and coming.” The third account, which is the longest and most interesting, is a report sent by the Prussian ambassador to London, Friedrich Bonet, to his sovereign. We learn that Baron Kilmanseck (Johann Adolf, Baron von Kielmansegg), who had been Handel’s protector in Hanover, organized the festivities of 17th July 1717 at his own expense, and that the concert cost him “a hundred and fifty pounds for the musicians alone”. Bonet’s account also gives the composition of the orchestra (“trumpets, horns, bassoons, oboes, German flutes, French flutes, violins and basses, but there were no singers”), and adds that the music had been specially written “by the famous Handel, a native of Halle and His Majesty’s principal court composer”.

For a long time Handel’s Water Music was his most popular instrumental work, but we possess neither the autograph manuscript nor an authentic first edition approved by the composer. The anecdote about the composition of the work is now well known. In 1712, Handel, who was Kapellmeister to the Elector of Hanover, had obtained permission from the latter to go to England, “on condition that he engaged to return within a reasonable time”. But Handel was still in London in 1714, when the Elector became King George I of England. According to John Mainwaring, the author of “Memoirs of the Life of the Late George Frederic Handel” (1760), the composer avoided all contact with the new sovereign until 22nd August 1715, when he had a new work executed during a royal procession on the Thames; it so captivated the king that he immediately pardoned him.

This story is attractive but unsubstantial. On 25th September 1714, just six days after landing at Greenwich, a Te Deum by Handel was given in the king’s presence and the same year he also attended a performance of Handel’s opera Rinaldo. If Handel was in disgrace, his music was not. And the only royal excursion on the river with music by Handel that we know of did not take place until 17th July 1717. There are three contemporary accounts of this event. The first two appeared in English newspapers. The Political State of Great Britain of 1717 reports that, on the evening of Wednesday 17th July, the king sailed to Chelsea “with excellent Musick organized by Baron Kilmanseck for his entertainment”; at three o’clock in the morning, he sailed back to Whitehall, and from there went on to St James’s palace. The Daily Courant for 19th July speaks of “the Musick, in which fifty instruments of all kinds played, throughout the journey from Lambeth the most agreeable symphonies composed especially for the occasion by Mr Handel. They pleased His Majesty so much that they were played three times, going and coming.” The third account, which is the longest and most interesting, is a report sent by the Prussian ambassador to London, Friedrich Bonet, to his sovereign. We learn that Baron Kilmanseck (Johann Adolf, Baron von Kielmansegg), who had been Handel’s protector in Hanover, organized the festivities of 17th July 1717 at his own expense, and that the concert cost him “a hundred and fifty pounds for the musicians alone”. Bonet’s account also gives the composition of the orchestra (“trumpets, horns, bassoons, oboes, German flutes, French flutes, violins and basses, but there were no singers”), and adds that the music had been specially written “by the famous Handel, a native of Halle and His Majesty’s principal court composer”.

+ information in the CD booklet

MARC VIGNAL

Translated by Mary Pardoe

Share