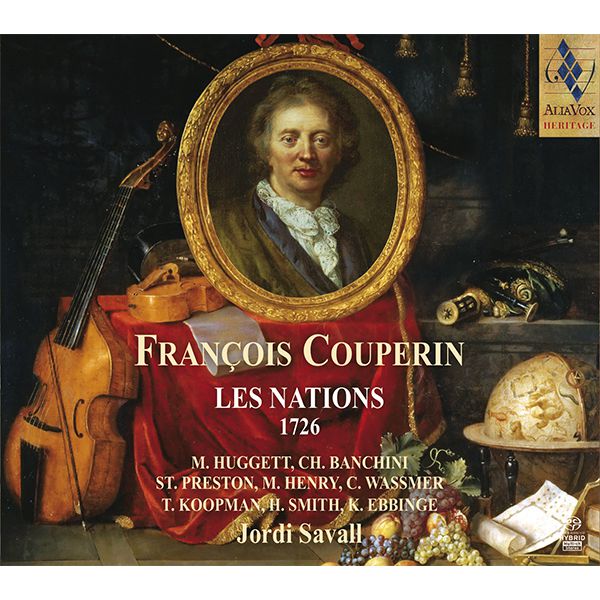

FRANÇOIS COUPERIN

Les Nations

Jordi Savall

Alia Vox Heritage

21,99€

2 CD

Born in 1668, François Couperin was the only son of Charles Couperin, the harpsichordist and organist at the old Parisian Church of Saint-Gervais. There had been an organ at the church since the 14th century, and in the 16th century it had two. The organ at the church in 1668 (the fourth) had been built in 1601, and after several refurbishments and improvements, it was one of the finest instruments in the kingdom. François Couperin’s father had two brothers, François and the eldest, Louis, a brilliant musician, who very quickly earned a place as organist at Saint-Gervais, as well as several charges in the King’s Music. When he died in 1661, Charles succeeded him as organist at Saint-Gervais; he was married the following year and in 1668 his only child was born, the second François Couperin in the family, who would come to be known as Le Grand.

François Couperin the Great

Born in 1668, François Couperin was the only son of Charles Couperin, the harpsichordist and organist at the old Parisian Church of Saint-Gervais. There had been an organ at the church since the 14th century, and in the 16th century it had two. The organ at the church in 1668 (the fourth) had been built in 1601, and after several refurbishments and improvements, it was one of the finest instruments in the kingdom. François Couperin’s father had two brothers, François and the eldest, Louis, a brilliant musician, who very quickly earned a place as organist at Saint-Gervais, as well as several charges in the King’s Music. When he died in 1661, Charles succeeded him as organist at Saint-Gervais; he was married the following year and in 1668 his only child was born, the second François Couperin in the family, who would come to be known as Le Grand.

As Pierre Citron tells us in his fine portrait of François Couperin, “The child’s early years unfolded on the street Monceau Saint-Gervais, at the old house reserved for the organist; but it was at the adjoining church itself that he was to spend most of his time. From infancy, the sound of the organ resonating beneath the church vaults was an inseparable part of him. His father would place the child’s hands on the keyboard even before he could speak; from the outset, he took pride in knowing that the solemn harmonies to which the congregation bowed during the church services issued from his father’s hands. Sitting in the organ loft above the priest in front of the altar, higher than the preacher in his pulpit, hidden from view during the service, all the more venerable because of his mysterious presence, his father must have seemed to him almost divine. In fact, religion and music were inseparable for the child; devoting his whole life to music must have been his first act of faith. It was therefore logical that his life’s goal was to be the organist of Saint-Gervais, like his uncle and his father before him.”

+ information in the CD booklet

JORDI SAVALL

Budapest / Bellaterra, June, 2018

Translated by Jacqueline Minett

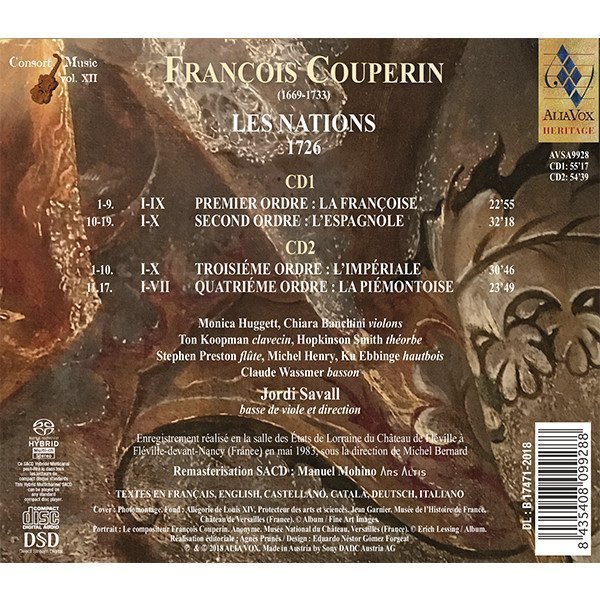

Post scriptum. The project to perform the four “orders” comprising the sonades and the corresponding suites using period instruments was born in the early 1980s. In those days, I taught viola da gamba and chamber music at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis in Basel and collaborated with various ensembles that were pioneers in the rediscovery of the early music heritage: Michel Piguet’s Ensemble Ricercare in Zurich, Trevor Pinnock’s English Concert in London, La Petite Bande with Gustav Leonhardt, and the nucleus of musician friends with whom I recorded, beginning in 1975, for the EMI Electrola and Astrée labels: Hopkinson Smith and Ton Koopman, soon joined by Monica Huggett and Chiara Banchini, two wonderful baroque violinists, and an exceptional team of wind instruments: Stephen Preston (transverse flute), Michel Henry and Ku Ebbinge (oboe), and Claude Wassmer (bassoon). It was thanks to this true “Réunion des Goûts” that we were able to put together the ideal team for our project. Then came the intense rehearsals, the concerts, and finally the recording in the Salle des États de Lorraine at the Château de Fléville-devant-Nancy, for Michel Bernstein’s Astrée label in May, 1983. That was the seed which, six years later, would give birth to the ensemble Le Concert des Nations during the preparation of the concerts and the recording of the programme devoted to Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s Canticum Beate Virgine.

Share