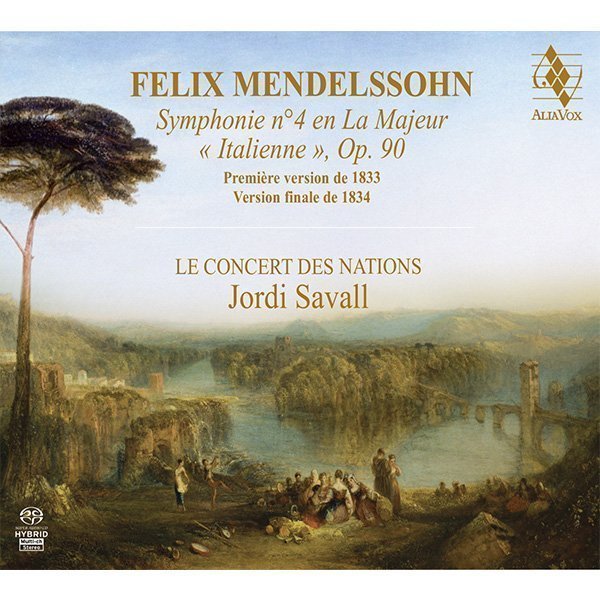

FELIX MENDELSSOHN

Symphonie nº4 en La Majeur

Jordi Savall, Le Concert des Nations

17,99€

ALIA VOX

AVSA9955

Total: 59’49

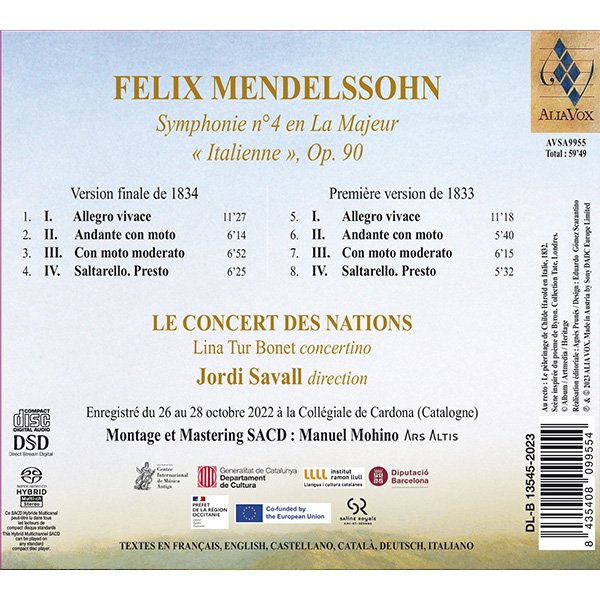

FELIX MENDELSSOHN

Symphonie nº4 en La Majeur

“Italienne”, Op.90

Version finale de 1834

1. I. Allegro vivace 11’27

2. II. Andante con moto 6,14

3. III. Con moto moderato 6,52

4. IV. Saltarello. Presto 6,25

Première version 1833

5. I. Allegro vivace 11’18

6. II. Andante con moto 5,40

7. III. Con moto moderato 6,15

8. IV. Saltarello. Presto 5,30

LE CONCERT DES NATIONS

Lina Tur Bonet concertino

JORDI SAVALL direction

Enregistré du 26 au 28 octobre 2022 à la Collégiale de Cardona (Catalogne)

Montage et Mastering SACD : Manuel Mohino (Ars Altis)

_

FELIX MENDELSSOHN

Italian Symphony

1833-1834

An exceptional traveller in search of light and joy

The fact that the young Mendelssohn’s first major solo trip at the age of 21 began with a visit to Goethe in Weimar allows us to imagine that the journey he undertook to his long-awaited discovery of Italy was inspired by the one Goethe had made to that country forty-five years earlier, which he recounted in his Italian Journey (Italienische Reise). What he writes about the visit at the end of his first letter dated 21 May 1830 is both enlightening and deeply moving: “I would have to be a fool to regret the time that I spent with him. Today, I am to play him some Bach, Haydn and Mozart and take him up to the present day, as he puts it. Besides, I have conscientiously done my job as a traveller.” With these words, he affirms his desire to confront others and the events of the past, as well as the modernity of his own time.

“Mendelssohn had just turned twenty-one, (Abraham-Auguste Rolland tells us in his preface to the first French edition of Mendelssohn’s letters, published in 1864) when his father, a wealthy Berlin banker and a man distinguished as much by his intelligence as his kindheartedness, decided to send him on a trip which would, so to speak, mark the young man’s coming of age. “Go,” he told him, “visit Germany, Switzerland, Italy, France and England; study these different countries and choose, the one you like best to settle there; make yourself known, show what you are capable of, so that, wherever you settle, you will be welcomed, and people will take an interest in your work.” Accordingly, Mendelssohn left in May1830 and did not return until June 1832, after having entirely fulfilled the programme set out by his father.

+ information in the CD booklet

JORDI SAVALL

Bellaterra, 3 July 2023

Translated by Jacqueline Minett

Share