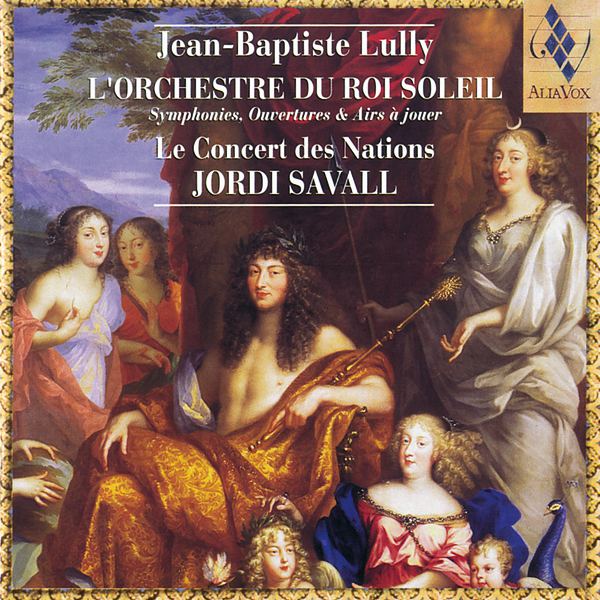

L’ORCHESTRE DU ROI SOLEIL

Jean-Baptiste Lully

17,99€

Out of stock

Ref: AVSA9807

- Jordi Savall

- Le Concert Des Nations

- Manfredo Kraemer

The years from 1670 to 1673 mark one of those crossroads at which history in general, and the history of art in particular, sometimes judiciously brings together just the right combination of people, events and even instruments. In fact, the events of those years were to have major consequences, not only for the future of French music, but also, to a certain extent, for Western music as a whole.

Firstly, the people; and, chief among them, the king. Louis XIV himself contributed in several ways. There was his thirst for glory, the like of which has rarely been seen in other monarchs. There was also his genuine and discerning love for all the arts, but especially for music and dance. Accordingly, he made the latter two art forms the favourite instruments of his “désir de gloire” and gave artists in these fields virtually unlimited resources with which to create their works. Then there was Lully, the beneficiary of the king’s munificence. Although one might criticise his attitude towards music (like Louis XIV’s own attitude towards the arts) as dictatorial, it is nevertheless a fact that no other musician (not even Wagner, whose royal patron was Ludwig II of Bavaria) ever received from his sovereign such an abundance of material, financial and moral support, and it was this power which would enable Lully to influence the destiny of music in the way that he did.

+ information in the CD booklet

PHILIPPE BEAUSSANT

Translated by Jacqueline Minett

Share