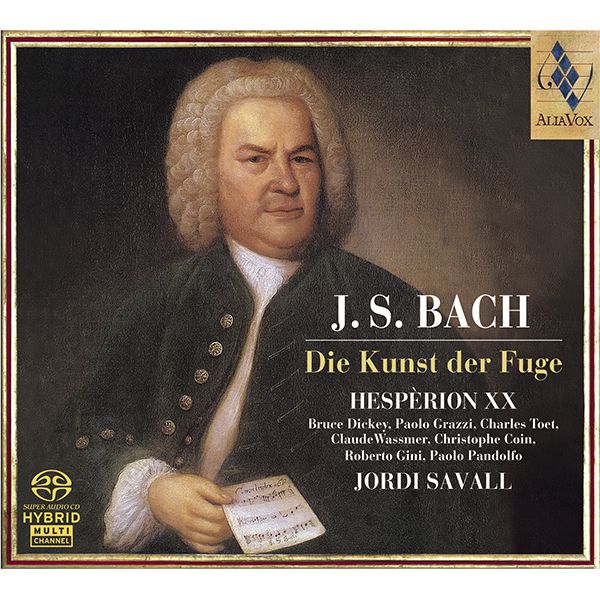

J.S BACH

Die Kunst der Fuge

Hespèrion XXI, Jordi Savall

21,99€

Ref: AVSA9818

- Jordi Savall

- Hespèrion XXI

More than two centuries after its composition, Johann Sebastian Bachs The Art of fugue is still a work that is full of mystery. Too “modern” for its own time, not understood by the Romantics, unjustly regarded as purely theoretical by certain musicologists at the beginning of the twentienth century, it is now finally recognized as one of the highest musical achievements of all time. Its rightful recognition as such has not, however, put and end to the various debates, nor has it resolved certain problems about its performance, the choice of instruments or instrumentation, the order of the counterpoints, the problems concerning the unfinished fugue, and naturally, the question of articulation, tempo dynamics, ornamentation, etc.

Historically, two options have been considered: one involves the use of keyboard instruments, adding a second one for counterpoints 19a and b (which replace counterpoints 13a and b); the other involves the use of an instrumental ensemble of the period which would be able to respect the original tone. It is more than likely that Johann Sebastian Bach knew works like the Fugues et caprices a quatre parties by François Roberday (1660) since Forkel, his principal biographer, relates that before composing The Art of fugue, he made a careful study of the earlier works of the French organists who were masters of harmony and fugue, according to the tradition of the time. We should stress two important points, both of which are mentioned in the Preface to Roberday’s work. The first is that having an open score in four parts does not exclude the possibility of playing this music on the organ or harpsichord. Tradition in fact dictated that contrapuntal works written for these instruments should be noted in this way “since the Parts being all together, and yet distinguished from one another, may the more easily be examined separately and the relationship they each have to one another more easily be seen”. The second point is that “the other advantage was that if one wished to play the Pieces of Music on viols or other similar Instruments, each player would find his Part separated from the others”.

+ information in the CD booklet

JORDI SAVALL

Basel, 1986/2001

Translated by Jacqueline Minett

Share