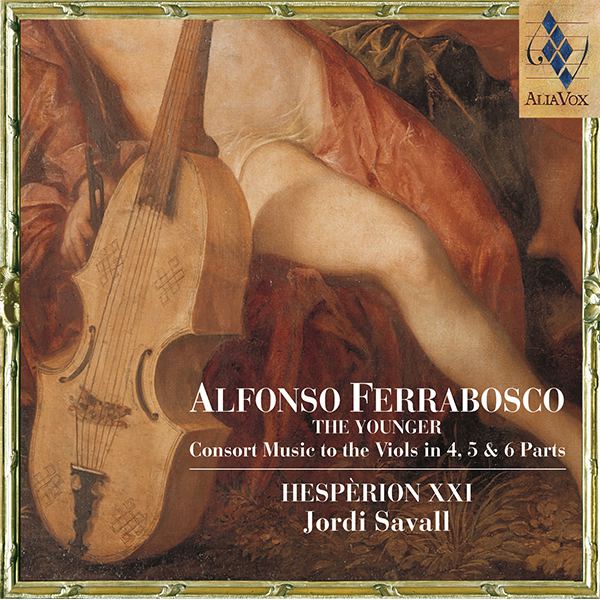

ALFONSO FERRABOSCO

THE YOUNGER

Consort to the Viols 4, 5, & 6 Parts

Hespèrion XXI, Jordi Savall

15,99€

Ref: AV9832

- Jordi Savall

- Hespèrion XXI

Alfonso Ferrabosco the younger (ca.1575-1628) came from a long line of musicians. His talented, Italian-born father, Alfonso Ferrabosco, had a meteoric career in Elizabethan England, where he gave a new zest to apathetic English society by importing musical techniques from Italy. The first major hurdle that confronted his son, the young Ferrabosco, who was a composer, violist, lutenist and singer, was being held up for comparison with his illustrious father.

“I am not made of much speach” was Alfonso Ferrabosco’s own gauntlet, tossed in the world’s face, when introducing his music in print. That hauteur mixed with reserve (“Value me as you will” in almost as many words), suggesting that one’s reputation is a trifle for others to debate, makes an unusual mixture. Posterity is naturally taken unawares. But English musical manuscripts bear witness to his status as the court composer in his time, by listing him casually just as Alfonso or AF. Then there are contemporary opinions to quote which, in words almost as terse as his own, pay him enormous respect. The playwright Ben Jonson, his collaborator in court masques, called him “a Man, planted by himselfe, & mastring all the spirits of Musique”. Jonson was a careful word-smith, sparing with his praise; he wrote not one but two separate laudatory poems for Ferrabosco’s published collections. But it is a shame that no portrait of him is known to exist, in this era when musicians were increasingly wearing a public face as virtuosi performer-composers; also, that there is the usual scarcity of biographical material. It takes imagination to picture him. Perhaps he should have the carefully dishevelled locks of the creative artist; just the way in which genius is given its full measure in the engravings of a comparably creative talent, Frescobaldi, that open his published works. The song-writer and poet Thomas Campion came the nearest to a pen-sketch of Ferrabosco, calling him “Old Alfonso’s Image living” – but that, however affectionately meant, is a twisted compliment in the long term, since no man can relish being matched against the icon of a famous father. And so his music, under-rated for so long since his own century, must speak for him, in its own language. The best of it has a monumental sculptural quality, and that can be daunting: it is hard to “walk around”. In fact in the fragments of a life that are visible, his deprived upbringing and the acclaim that followed, do somewhat explain the heroism as well as the reserve in this output.

+ information in the CD booklet

Share