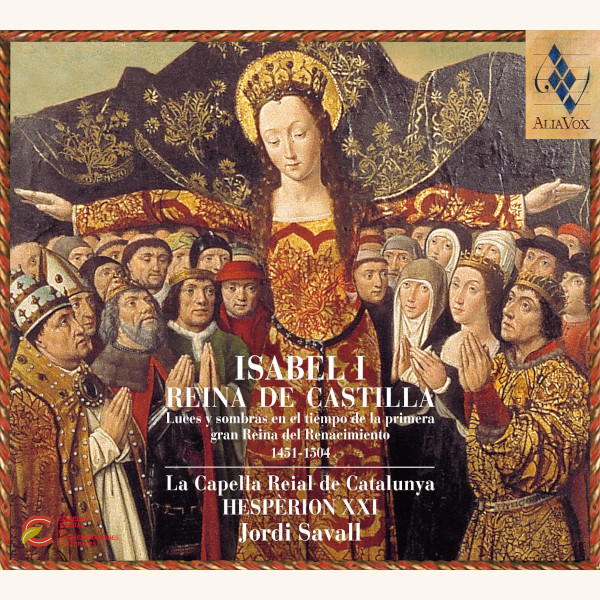

ISABEL I REINA DE CASTILLA

1451-1504 · Luces y sombras

Hespèrion XXI, Jordi Savall, La Capella Reial de Catalunya

17,99€

Reference: AV9838

- La Capella Reial de Catalunya

- Hespèrion XXI

- Jordi Savall

At the time of Isabella’s birth in 1451, the Iberian Peninsula was divided into three separate kingdoms: Aragon, Castile and Portugal. The balance of power was maintained thanks to a complex interplay of wars, short-term political alliances and marriages between the three royal houses. All three kingdoms were engaged in internal struggles between the authority of the crown and the privileges of the great nobles. As trade increased, the growth of cities meant that far-reaching reforms and the establishment of centralised government, with a single centralised tax system, became a priority. That, in turn, put an end to the autonomy of the powerful aristocratic landowners.

Daughter of John II of Castile and his second wife, Isabella of Portugal, the young Isabella had a brother, Henry IV, who came to the throne of Castile when King John died in 1554. The ineffectual Henry had a daughter Joanna, known as “la Beltraneja” because she was commonly believed to be the child not of Henry but of his favourite, Beltrán de la Cueva. The question of the royal succession therefore remained unsettled; finally, in 1468, Isabella was designated Princess of Asturias and heir to the Castilian throne. Isabella was now faced with the difficult choice of a suitable husband in terms of the existing political ground rules, a choice which would have vital implications for the geo-political future of the Peninsula. Contrary to the wishes of her brother, Isabella chose the young Prince Ferdinand, King of Sicily and heir to the Crown of Aragon. Her decision met with the hostility of both the French and the Portuguese, who did not take kindly to the threat of a powerful alliance between Castile and Aragon.

+ information in the CD booklet

Share