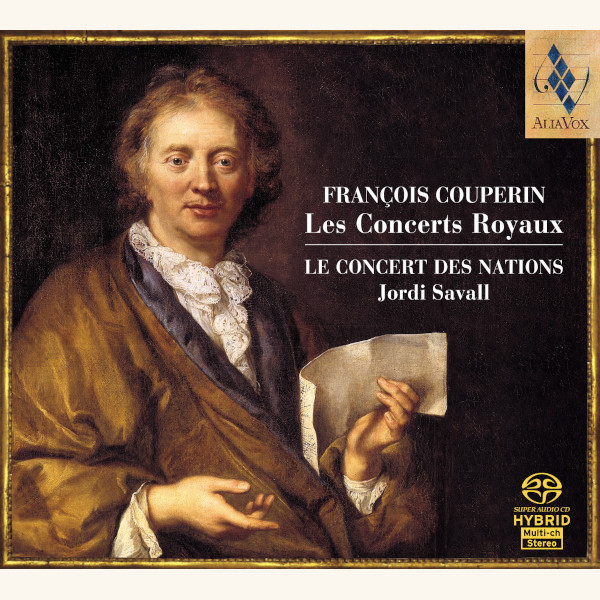

FRANÇOIS COUPERIN

Les Concerts Royaux

Jordi Savall, Le Concert des Nations

17,99€

Out of stock

Ref: AVSA9840

- Le Concert des Nations

- Jordi Savall

Following our versions of François Couperin’s “Pièces de Viole”(1728), “Les Nations” (1726) and “Les Apothéoses” (1724), recorded in 1976, 1985 and 1986, respectively, we now offer our interpretation of these “Concerts Royaux”, mindful of the responsibilities that the composer laid at the performing musician’s door. Although he points out that these pieces “are of a kind quite different from those I have previously published”, adding that “They may be played not only on the harpsichord, but also the violin, the flute, the oboe, the viol, and the bassoon”, he leaves the instrumentation of each piece and Concert entirely up to us. Couperin tells us that “These pieces were executed by Messieurs Duval, Philidor, Alarius and Dubois: I myself played the harpsichord”. One could hardly imagine more precise indications than those concerning the instruments given in the preface, together with the roles of the musicians as described by Couperin himself. It is in this context that we have re-conceived the instrumentation of each Concert, the choice of instruments differing from piece to piece to ensure the best expression, as well as the greatest definition, of the musical character of each one:

+ information in the CD booklet

Jordi Savall

Share