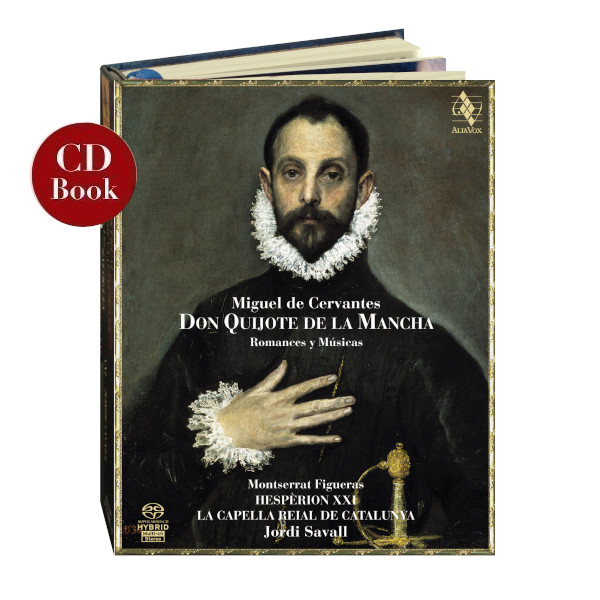

DON QUIJOTE DE LA MANCHA

Romances y Músicas

Hespèrion XXI, Jordi Savall, La Capella Reial de Catalunya, Montserrat Figueras

25,99€

Ref: AVSA9843

- Hespèrion XXI

- La Capella Reial de Catalunya

- Jordi Savall

Amid the plethora of eulogies and tributes published to mark the fourth centenary of The Quixote, few will have addressed in any depth the musical facet of Miguel de Cervantes’s genius, and still fewer will have paused to reflect that Cervantes’s literary greatness brought him as little worldly success as his hero’s greatness of spirit afforded him. Like our musicians of the past, whose memory, even in the 21st century, is still buried under the successive layers of Romanticism and Modernism, let us not forget, in the midst of all the celebrations, that Miguel de Cervantes, to whose musical dimension we now pay tribute, was not only misunderstood in the Spain in which he lived, but also disparaged and humiliated by his contemporaries.

Only a writer with excellent musical training and experience and, moreover, one who had a thorough knowledge of the nature and practice of music, of both the ancient and contemporary ballad repertories, of song and dance, as well as the musical instruments used in his day, could have incorporated such a wealth of precise information about everyday musical practice into his narratives. For Cervantes, music is always the purest form of expression of individual feeling. The numerous sounds, both musical and environmental, that are always described in profuse detail, fill and indeed quicken his characters’ lives at moments of heightened emotion. Music can evoke peace and joy, melancholy and sadness, but it can also enchant and bewitch the listener, thanks to the highly intimate and personal nature of song and its own particular beauty and expression. Together, the music and the ballads transport us to a fantastic world in which our ancestral memory of history and myth inspires or encourages to understand or bear, and ultimately to sublimate and overcome the disappointments and setbacks of our daily lives. That is why music is always such a crucial element in Cervantes’s narrative, taking us into that magical dimension which goes far beyond what can be expressed or suggested by words alone.

+ information in the CD booklet

JORDI SAVALL

Bellaterra, Summer 2005

Share