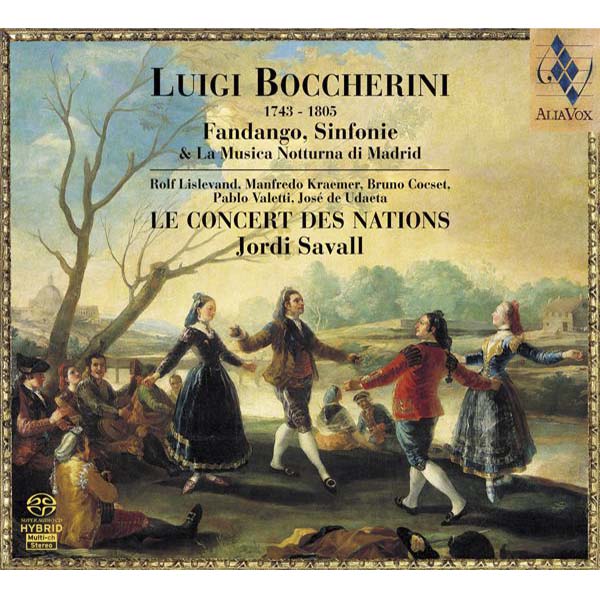

LUIGI BOCHERINI

Fandango, Simfonie & Musica Notturna di Madrid

Jordi Savall

17,99€

Ref: AVSA9845

- Jordi Savall

- LE CONCERT DES NATIONS

Although he composed carols, cantatas, oratorios, a mass, motets, the so-called academic (concert) arias for soprano and orchestra to texts by Metastasio and a zarzuela to a libretto by Ramón de la Cruz, most of Boccherini’s output was instrumental music. That was quite unusual in the 18th century, especially in his native Italy, the cradle of opera and a hotbed of both sacred and secular vocal music. Within his large volume of works, Boccherini’s chamber music is pre-eminent, among other things because the composer’s first Spanish period was spent in the service of the King Charles III’s brother, the Infante Don Luis, who, as a great music lover, employed a string quartet made up of members of the Font family. The addition of Boccherini to the quartet explains the unusually high number and quality of string quintets with two cellos among his works.

Boccherini wrote chamber music not only for bowed string instruments but also for keyboard – harpsichord and piano – and guitar, in the latter case as a result of his association with a Catalan nobleman living in Madrid, Don Borja de Riquer, the Marquis de Benavent. The quintets with guitar are arrangements of pieces previously scored for string quartet with an additional cello, as in the case of Quintet No. 7 in D Major, G. 448, or for string quartet and piano, as in Quintet No. 7 in E Minor, G. 451. Both works have survived thanks to a copy of the manuscripts made by the Roussillon-born guitarist and composer François de Fossa (1775-1849), who enlisted and served in the Spanish army 1797-1803. A great devotee of the guitar, it is more than likely that he visited Boccherini in Madrid and took part in the musical evenings hosted by the Marquis de Benavent at his mansion in Atocha Street. The influence of Boccherini is clearly evident in Fossa’s Three Quartets for two guitars, violin and cello, Op. 19.

+ information in the CD booklet

ANDRÉS RUIZ DE TARAZONA

(1) Speck, Christian: Boccherini’s Concert Arias. Mozart-Jahrbuch 2000, pp. 225-244. Speck is the author of a critical edition of the complete symphonies of Luigi Boccherini.

(2) Una cosa rara, ossia belleza ed onestà, by Vicente Martín y Soler, was recorded by Le Concert des Nations under the direction of Jordi Savall in 1991 (Astrée/Auvidis).

Share