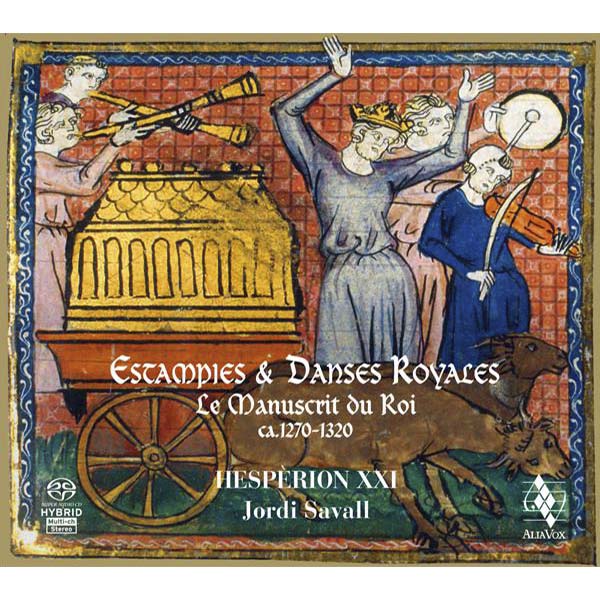

ESTAMPIES & DANSES ROYALES

Le manuscrit du roi ca.1270-1320

Hespèrion XXI, Jordi Savall

17,99€

Reference: AVSA: AVSA9857

- Hespèrion XXI

- Jordi Savall

“The estampie is a musical composition without words which has a complex melodic progression (habens difficiles concordantiarum discretionem) and which is divided into points (puncti). Because of its difficulty, it totally absorbs both the performer and the listener, and often distracts the minds of the rich from wicked thoughts” – an echo of the profound and abiding conviction of those early minstrels and poet-musicians, who even then were aware of the powerful influence that music can have in the education of human beings.

As we stand at the dawn of the 21st century, more than seven hundred years separate us from the age when this fascinating music was created and performed for the first time. Still breathtakingly mysterious and vibrantly beautiful, it is one of the earliest surviving collections of medieval instrumental music, preserved thanks to a written source dating from the period. These pieces still surprise and move us today, thanks to their rhythmic beat and poetic charm which, in spite of the seven centuries of amnesia separating them from us, remain astonishingly clear and captivating. The age of crusading King Louis IX was at an end and Philip IV, called “the Fair”, was now King of France (1285-1314); indeed, the very manner of writing and the notation of the manuscript confirm that it was probably at the end of the 13th century, or at the very latest around 1310, when an anonymous musician decided to copy down in this fine “Manuscrit du Roi” (mss. français 844, Bibliothèque Nationale, also known as “Chansonnier du Roi “), the ESTAMPIES ET DANSES ROYALES, which we have restored and re-interpreted in full in this new recording, using period instruments.

+ information in the CD booklet

JORDI SAVALL

Paris, January 2008

Translated by Jacqueline Minett

Share