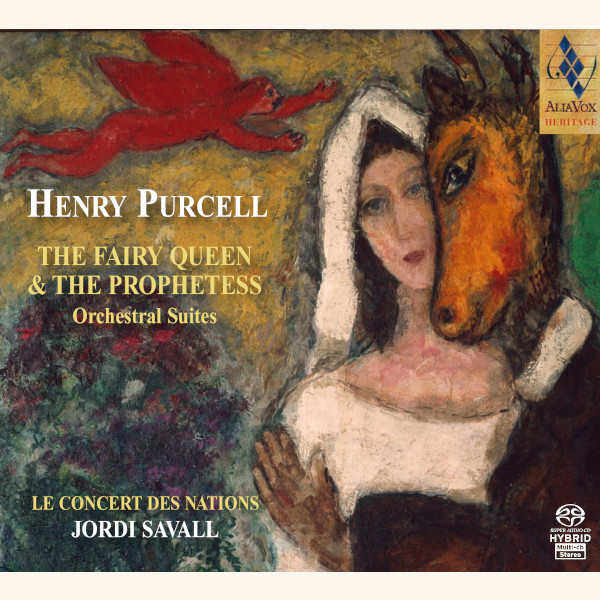

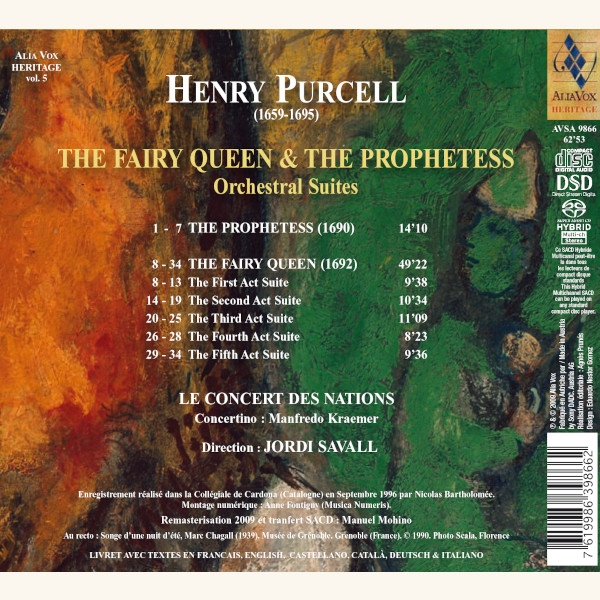

HENRY PURCELL (1659-1695)

The Fairy Queen & The Prophetess

Jordi Savall, Le Concert des Nations

Alia Vox Heritage

15,99€

Reference: AVSA9866

- Le Concert des Nations

- Jordi Savall

The English were latecomers to the opera. Following the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, one might have expected the theatrical establishment to embrace the new genre enthusiastically: after all, things foreign were once again in fashion. Charles II himself established a troupe of string players in frank imitation of Louis XIV’s Vingt-Quatre Violons du Roi, while in France itself, Italian opera, having been successfully transplanted, soon thrived in its new soil. But for some reason, the first attempts at popularizing opera in England (whether in Italian or in the vernacular) were failures. Instead, the practice of introducing incidental music within plays and masques assumed increasing importance. Such music could either set the action (in the manner of an Overture), comment upon it (in the case of vocal numbers), or else accompany danced items; but in any case its relationship to the plot was often peripheral. Midway between this simpler kind of incidental music and the full-blown opera stands the semi-opera, an indigenous genre borne largely out of fashionable aversion to opera itself: after all, the expense of a fully-staged production of The Fairy Queen would have been at least comparable to operatic extravaganzas on the continent.

But all technicalities aside, the varied orchestration, the inexhaustible flights of fancy, the deft touches, may be Purcell’s response to the constant intrusion into his librettos of the supernatural. Throughout the semi-operas (and in Dido, of course), gods, faeries, spirits fair or foul intervene in human affairs. This theme finds its most tragic expression in Dido, but its magical and comic aspects are even more full explored in The Fairy Queen. Thus, the echo sequences from The Fairy Queen put a magical construction on one of the baroque’s musical commonplaces, while the appearance of Fairies, Furies and Green Men call forth striking, buoyant gestures. The flip-side of magic is exoticism, of which The Fairy Queen provides several examples. Yet it is through costumes and choreography that exoticism must have struck Purcell’s contemporaries, for there is nothing particularly simian about the Monkeys Dance, and the music of Chinese ballet can hardly have been familiar to the Restoration Londoner. The concept of the stage work as divertissement, dramatic though not necessarily representational, is paramount; the burdens of narrative, of psychological characterization, of verisimilitude are not the music’s concern. In that sense, the semi-operas differ from opera proper, with Dido and Aeneas serving as a harbinger of things to come.

+ information in the CD booklet

FABRICE FITCH

Share