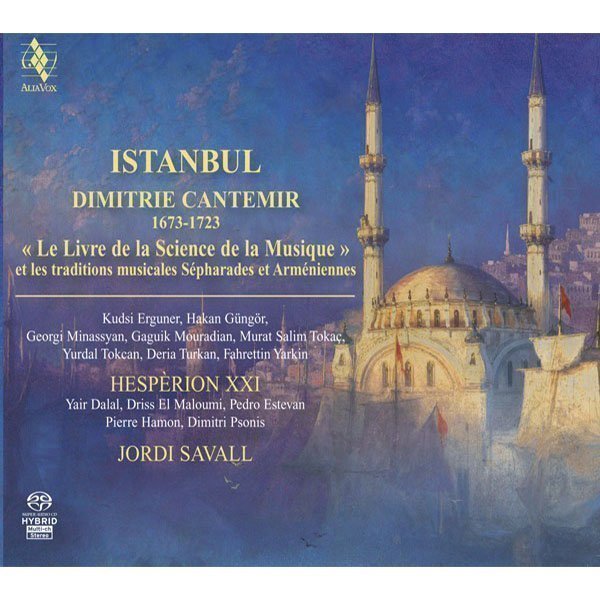

ISTANBUL

Dimitrie Cantemir

1673-1723

Hespèrion XXI, Jordi Savall

15,99€

Reference: AVSA9870

- Hespèrion XXI

- JORDI SAVALL

Dimitrie Cantemir’s Book of the Science of Music, which has served as the historical source for our recording, is an exceptional document in many ways; first, as a fundamental source of knowledge concerning the theory, style and forms of 17th century Ottoman music, but also as one of the most interesting accounts of the musical life of one of the foremost Oriental countries. This collection of 355 compositions (including 9 by Cantemir), written in a system of musical notation invented by the author, constitutes the most important collection of 16th and 17th century Ottoman instrumental music to have survived to the present day. I first began to discover this repertory in 1999, during the preparation of our project on Isabella I of Castile, when our friend and colleague Dimitri Psonis, a specialist in Oriental music, suggested an old military march from the collection as a musical illustration of the date commemorating the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman armies of Mahomet II.

At the time of Dimitrie Cantemir (1673-1723), the city which stands at the crossroads of the continents of Europe and Asia, ISTANBUL for the Ottomans and CONSTANTINOPLE for the Byzantines, already marked a veritable high point in history. Despite the memory and very palpable presence of the old Byzantium, it had become the true heart of the Muslim religious and cultural world. An extraordinary melting-pot of peoples and religions, the city has always been a magnet for European travellers and artists. Cantemir arrived in the city in 1693, aged 20, initially as a hostage and later as a diplomatic envoy of his father, the ruler of Moldavia. He became famous as a virtuoso of the tanbur, a kind of long-necked lute, and was also a highly-regarded composer, thanks to his work Kitab-i ilm-i musiki (The Book of the Science of Music), which he dedicated to Sultan Ahmed III (1703-1730).

Such is the historical context of our project on “Dimitrie Cantemir’s The Book of the Science of Music and the Sephardic and Armenian musical traditions”. We aim to present the “cultivated” instrumental music of the 17th century Ottoman court, as preserved in Cantemir’s work, in dialogue and alternating with “traditional” popular music, represented here by the oral traditions of Armenian musicians and the music of the Sephardic communities who had settled in the Ottoman empire in cities such as Istanbul and Izmir after their expulsion from Spain. In Western Europe, our cultural image of the Ottoman Empire has been distorted by the Ottoman Empire’s long bid to expand towards the West, blinding us to the cultural richness and, above all, the atmosphere of tolerance and diversity that existed in the Empire during that period. As Stefan Lemny points out in his interesting essay on Les Cantemir, “in fact, after taking Constantinople, Mahomet II spared the lives of the city’s Christian population; what is more, a few years later he encouraged the old aristocratic Greek families to return to the district known as Fener or Phanar, the hub of the former Byzantium.” Later, under the reign of Suleyman – the Golden Age of the Ottoman Empire – contacts with Europe intensified on a par with the development of diplomatic and trade relations. As Amnon Shiloah reminds us in his excellent book La musique dans le monde de l’islam: “Although Venice had a permanent diplomatic mission to Istanbul, the Empire turned its sights towards France. Towards the end of the 16th century, the treaty which was signed in 1543 between Suleyman and ‘the Christian king” Francis I of France was a decisive factor in the process of rapprochement which led to greater interaction. On that occasion, Francis I sent Suleyman an orchestra as a token of his friendship. The concert given by the ensemble appears to have inspired the creation of two new rhythmic modes which then entered Turkish music: the frenkcin (12/4) and the frengi (14/4).”

+ information in the CD booklet

JORDI SAVALL

Edinburgh, August 2009

Translated by Jacqueline Minett

P.S. I would like to thank Amnon Shiloah, Stefan Lemny and Ursula and Kurt Reinhard for their research and analysis on the history, music and the period, which I have used in documenting some of the sources in my commentary.

Share