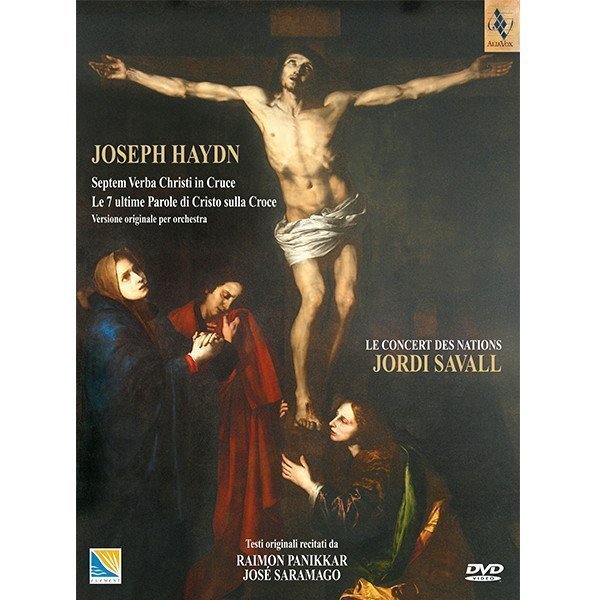

JOSEPH HAYDN

Septem Verba Christi in Cruce

Jordi Savall, Le Concert des Nations

17,99€

Referència: AVDVD9868

- Le Concert des Nations

- Jordi Savall

Joseph Haydn’s “The 7 Last Words of Christ on the Cross” is one of the most emblematic musical creations of the Age of Enlightenment. More than 200 years later, its spiritual message and expressive power are as vibrant and suggestive as ever. The wonderful Light emanating from each of these pieces remains undimmed, thanks to the composer’s creative genius, his rich inner life and his capacity for poetic/musical symbolism. Seven slow movements – eight if we count the Introduzione- wrought with such variety in terms of their musical invention, rhythms, dynamics, keys and themes, as well as their exceptionally rich palette of sound and expression, that we are totally oblivious to the fact that they are essentially very similar in terms of form and length. But, above all, there is one essential quality that makes this cycle of movements unique: the expressive mood remains one of supremely moving intensity and fervour throughout. Haydn explained his own vision of the work in the following words: “Each Sonata, or rather, each setting of the text, is expressed by instrumental music alone, but in such a way that it creates the most profound impression on even the most inexperienced listener.” (Letter dated 8th April, 1787, to his London publisher William Forster).

By the time he received this very special commission at the beginning of 1786, Haydn was already a famous composer, a well-known figure throughout the music world, but he was immediately fascinated by the extraordinary challenges posed by the project. In his autobiography, Maximilian Stadler (1748-1833) tells us that he was at Haydn’s house when the composer received the commission: “He also asked me for my opinion. I replied that I thought it would be best to begin by adapting the words to an appropriate melody, and then repeat that melody on instruments alone. And that is what he did, although I do not know if that was his own original intention”. In 1801, when Breitkopf & Hártel published the vocal version of the work, it appeared together with an explanatory text, quite plausibly in Haydn’s own words (although it mistakenly refers to the Cathedral, rather than the church of Santa Cueva, as the place where the work was to be performed), included by Haydn’s biographer, Georg August Griesinger (1769-1845), relating the context and circumstances in which the work was composed: “Some fifteen years ago I was requested by a canon of Cádiz to compose instrumental music on the seven last words of Christ on the Cross. It was customary at the Cathedral of Cádiz to produce an oratorio every year during Lent, the effect of the performance being not a little enhanced by the following circumstances. The walls, windows, and pillars of the church were draped with black cloth, and the solemn darkness was broken only by a single large lamp hanging from the centre of the roof. At midday, the doors were closed and the ceremony began. After a short service, the bishop ascended the pulpit, pronounced the first of the seven words and delivered a commentary on it. Then, he left the pulpit and prostrated himself before the altar, the ensuing interval being filled by music. The bishop then in like manner pronounced the second word, then the third, and so on, the orchestra following on the conclusion of each commentary. My composition was subject to these conditions, and it was no easy task to compose a succession of seven adagios lasting ten minutes each, without fatiguing the listeners.”

+ information in the CD booklet

Jordi Savall

Summer, 2007

Share