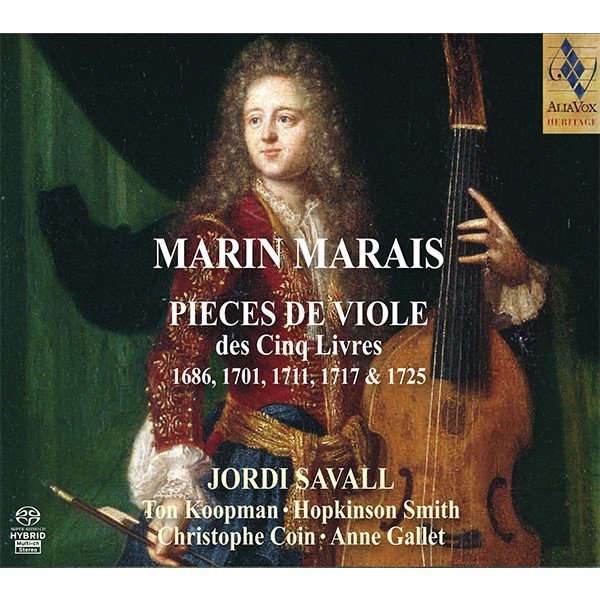

MARIN MARAIS

Pièces de viole des Cinq Livres

Jordi Savall

Alia Vox Heritage

32,99€

Referència: AVSA9872

- JORDI SAVALL

- Ton Koopman

- Hopkinson Smith

- Christophe Coin

Like many of his contemporaries, Marin Marais has paid the price of his proximity to some outstandingly brilliant musicians. Between Lully and Rameau we can still cite Charpentier, Delalande, Campra and François Couperin. But what about the others? The Destouches, Mouret and Marais pale beside the stars of a fertile era which was rocked by controversy. The school of harpsichordists and organists, who were no match for Lully’s vocal art, are still represented in the repertoire of present-day performers: D’Anglebert, Lebègue, Dandrieu, Grigny and Clérambault are still played on our instruments. But Marin Marais had the misfortune not only to compose operas in Lully’s domain, but also to devote the bulk of his art to an instrument which was being eclipsed by the advance of the violin family… namely, the VIOLA DA GAMBA or the BASS VIOL. And it is only recently that we have rediscovered the specific manner of playing this instrument as well as the composers who wrote for it.

Born on 31 May 1656, the son of a shoemaker, Marin Marais became a chorister at Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois in Paris, around the same time as another boy with a promising future, M.R. Delalande (1656-1726), who was to make his name as a composer of sacred music. At sixteen Marais left the choir school to become a pupil of Sainte-Colombe, a virtuoso on the viola da gamba, who had brought the instrument’s technique to such perfection that he could, in the words of H. Le Blanc, “imitate the most beautiful ornaments of the voice” (Défense de la Basse de Viole, 1740). The viola da gamba was, in fact, just beginning to enjoy popularity in France. In 1636, Marin Mersenne wrote in his Harmonie Universelle: “Those who have heard excellent performers and good ensembles of Viols, know that, except for good voices, there is nothing as ravishing as the languishing bow strokes which accompany the trills which are done on the fingerboard, but since it is no less difficult to describe their grace as that of a perfect Orator, they have to be heard to be understood.” The English school, introduced into France by Richelieu’s viol player, André Maugars, later helped to give the French viol its own technique and style, which masters like Sainte-Colombe brought to even greater perfection. Marin Marais took advantage of this teaching and soon surpassed his master. At the age of twenty he was engaged as Court Composer and in 1679 was appointed Musician in Ordinary to the King’s Chamber for the viol, a post that he continued to occupy until 1725, shortly before his death. His rise to fame was a rapid one: in 1680 he was cited, alongside his teacher, among the great virtuosi of the day. He divided his time between his duties at court, composition and teaching the viol.

+ information in the CD booklet

MARIE MADELEINE KRYNEN

Translated by Frank Dobbins

Share