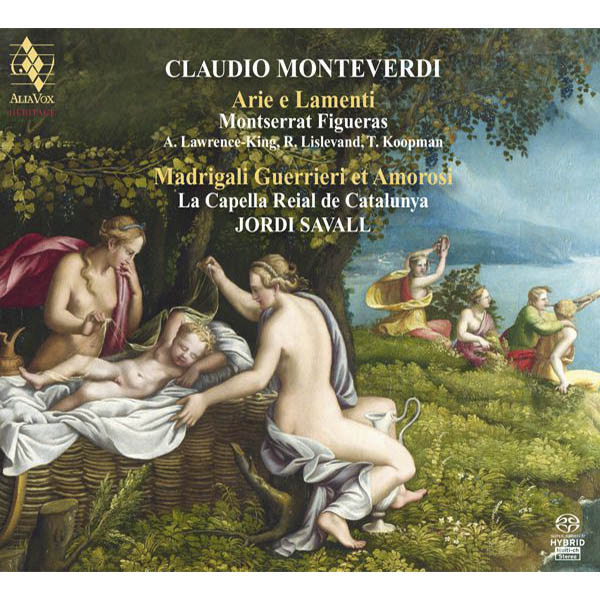

CLAUDIO MONTEVERDI

Arie e Lamenti

Jordi Savall, La Capella Reial de Catalunya, Montserrat Figueras

Alia Vox Heritage

15,99€

Out of stock

Reference: AVSA9884

- Montserrat Figueras

- La Capella Reial de Catalunya

- Jordi Savall

Among the eight books of madrigals published by Monteverdi between 1587 and l638, the last collection occupies a very special place. This collection, printed when the art of the madrigal, generally in five voices, which had indisputably reigned during at least one century over Italy and also north of the Alps, had finally relinquished its prominent position to lighter genres such as duets and cantatas, seems to be a farewell to the past; with its innovative phrasing grounded in philosophical views, it clears the way for a musical language focusing on the emotions which was to put its stamp on musical creation for a very long time.

MADRIGALI GUERRIERI ET AMOROSI

Among the eight books of madrigals published by Monteverdi between 1587 and l638, the last collection occupies a very special place. This collection, printed when the art of the madrigal, generally in five voices, which had indisputably reigned during at least one century over Italy and also north of the Alps, had finally relinquished its prominent position to lighter genres such as duets and cantatas, seems to be a farewell to the past; with its innovative phrasing grounded in philosophical views, it clears the way for a musical language focusing on the emotions which was to put its stamp on musical creation for a very long time.

It pays a final tribute to the magnificence of Italian literature, while already reflecting through sumptuous and imposing compositions the musical taste of the Viennese Imperial court.

This eighth book is dedicated to the Emperor, even if, given its troubled genesis, we still cannot be sure to which Emperor exactly. Monteverdi intended at first to dedicate his madrigal collection to Emperor Ferdinand the Second, leader of the Catholic league during the Thirty Years’ War. When the monarch died in 1637, while the work was still in press, his son succeeded him as Ferdinand the Third. Consequently, Monteverdi changed his previous dedication, placing as he explained in the foreword “at the son’s feet a present initially intended for the father”

+ information in the CD booklet

SILKE LEOPOLD

Translated by Marie Costa

Share