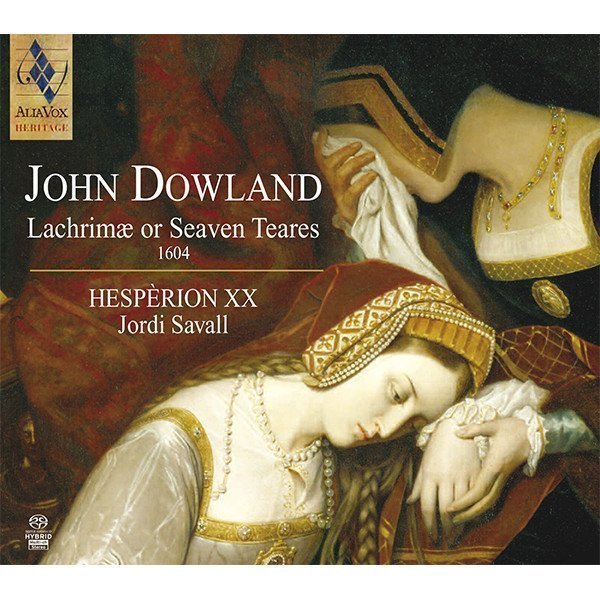

JOHN DOWLAND

Lachrimae or Seaven Teares

Hespèrion XXI, Jordi Savall

Alia Vox Heritage

15,99€

Referència: AVSA9901

- Jordi Savall

- HESPÈRION XXI

John Dowland was no less famous for his misfortunes than for his works. This subtle, elusive and strangely-behaved character led rather an adventurous life. Hailed as an Anglorum Orpheus (or “Orpheus of the English”) of almost divine powers, he inspired more comments and praise than most great musicians of his generation. To comply with legend, we were to associate him only with tears, sleep and gloom, in the gallery of Shakespearian heroes he could be placed somewhere between Hamlet and Jaques in As You like It. Although the legend may be partly based on truth, the musician himself contributed a great deal to it in his various writings; these are the confessions of a man full of dissonances, at once vulnerable and ambitious, ingenuous and haughty – an egocentric ever at odds with a world by which he felt himself rejected. Yet the dismal accents and sombre colours we readily associate with Dowland’s music may be less characteristic of his art than they are of a period which had been deeply shaken in its political security, religious faith and scientific beliefs. The man of the time, confronted with his duality as a terrestrial creature yearning for Eternity, was beset by doubts and dismay. It was such feelings that gave rise to what is sometimes called “17th century melancholy”. At the end of Elizabeth’s reign and through the Jacobean period, England, more than any other nation, was affected by this morbid wave: melancholy became the object of a new cult, to which the philosopher, the lover and the poet devoted themselves passionately… The common herd regarded it only as a precious convention, fit to be lampooned in the satires of the day; for sensitive souls, however, it proved to be one of the most fruitful sources of inspiration in a period that shone with the unique brilliance of Donne, Hilliard and Weelkes.

John Dowland was no less famous for his misfortunes than for his works. This subtle, elusive and strangely-behaved character led rather an adventurous life. Hailed as an Anglorum Orpheus (or “Orpheus of the English”) of almost divine powers, he inspired more comments and praise than most great musicians of his generation. To comply with legend, we were to associate him only with tears, sleep and gloom, in the gallery of Shakespearian heroes he could be placed somewhere between Hamlet and Jaques in As You like It. Although the legend may be partly based on truth, the musician himself contributed a great deal to it in his various writings; these are the confessions of a man full of dissonances, at once vulnerable and ambitious, ingenuous and haughty – an egocentric ever at odds with a world by which he felt himself rejected. Yet the dismal accents and sombre colours we readily associate with Dowland’s music may be less characteristic of his art than they are of a period which had been deeply shaken in its political security, religious faith and scientific beliefs. The man of the time, confronted with his duality as a terrestrial creature yearning for Eternity, was beset by doubts and dismay. It was such feelings that gave rise to what is sometimes called “17th century melancholy”. At the end of Elizabeth’s reign and through the Jacobean period, England, more than any other nation, was affected by this morbid wave: melancholy became the object of a new cult, to which the philosopher, the lover and the poet devoted themselves passionately… The common herd regarded it only as a precious convention, fit to be lampooned in the satires of the day; for sensitive souls, however, it proved to be one of the most fruitful sources of inspiration in a period that shone with the unique brilliance of Donne, Hilliard and Weelkes.

+ information in the CD booklet

CLAUDE CHAUVEL

Translated by Josine Monbet

Share