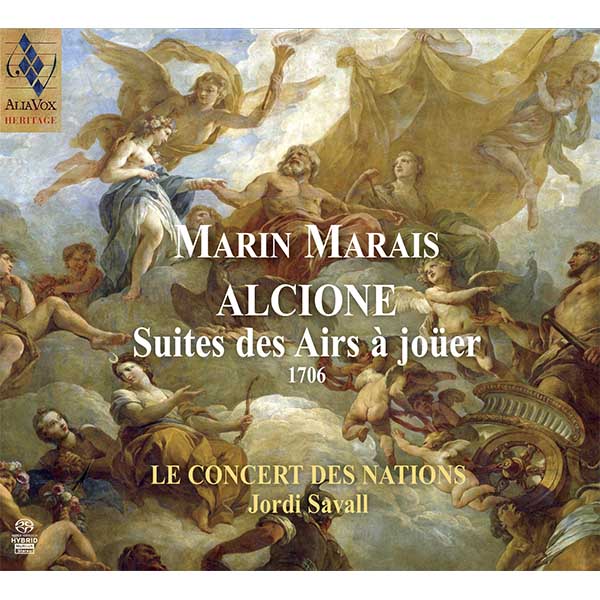

MARIN MARAIS

Alcione Suites des Airs à joüer (1706)

Jordi Savall, Le Concert des Nations

Alia Vox Heritage

15,99€

Refèrencia: AVSA9903

- Jordi Savall

- LE CONCERT DES NATIONS

On 18 February 1706, the opera (or tragédie en musique), Alcyone was given its first performance at the Palais Royal in Paris. The public response was immediately enthusiastic. It was to be Marin Marais’s greatest triumph. The composer, aged fifty, was at the height of his career. He had just replaced André Campra as “conducteur” at the Paris Opera, beating time for the numerous performers who were called upon to play in the pit or appear on stage.

On 18 February 1706, the opera (or tragédie en musique), Alcyone was given its first performance at the Palais Royal in Paris. The public response was immediately enthusiastic. It was to be Marin Marais’s greatest triumph. The composer, aged fifty, was at the height of his career. He had just replaced André Campra as “conducteur” at the Paris Opera, beating time for the numerous performers who were called upon to play in the pit or appear on stage.

Before honouring his new position with the performance of Alcyone, the former pupil of Sainte-Colombe had made a name for himself as a bass viol player quite early on, in 1676. His talents as an instrumentalist earned him a place in the Opera orchestra and in the Musique du Roi, and he took part in the grandiose performances of the operas of Lully, whose protégé he became. He soon began to compose not only numerous pieces for the bass viol, but also operas: an Idylle dramatique, performed in concert in the apartments of Versailles in 1686; then, in 1693, Alcide, written in collaboration with the son of the great Lully, Louis; Ariane et Bacchus in 1696; Alcyone, ten years later; and Sémélé, whose failure in 1709 led him to give up composing for the stage. He subsequently made a number of alterations to Alcyone for its revival in 1719. After his death in 1728, the opera was restaged in 1730, 1741, 1756, 1757 and 1771, which shows how popular the work was.

+ information in the CD booklet

JÉRÔME DE LA GORCE

Translated by Mary Pardoe

Share