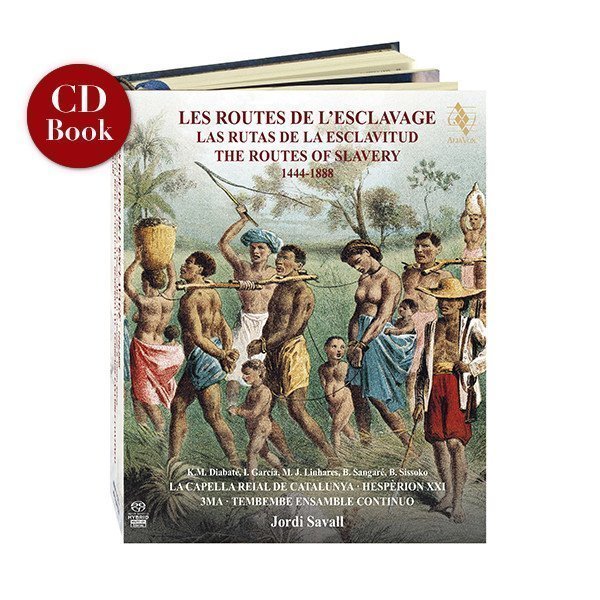

LES ROUTES DE L’ESCLAVAGE

1444-1888

Hespèrion XXI, Jordi Savall, La Capella Reial de Catalunya

32,99€

We firmly believe that the advantage of being aware of the past enables us to be more responsible and therefore morally obliges us to take a stand against these inhuman practices. The music in this programme represents the true living history of that long and painful past. Let us listen to the emotion and hope expressed in these songs of survival and resistance, this music of the memory of a long history of unmitigated suffering, in which music became a mainspring of survival and, fortunately for us all, has survived as an eternal refuge of peace, consolation and hope.

Slavery remembered

1444 – 1888

Critics

”

" The music spans four and a half centuries, but the book’s panorama presents the history of global slavery through five millennia, as described by academic essays plus panoramic surveys of this perennial and ubiquitous abuse. "

BBC Music Magazine. August 2019. Michael Church

”

"Un hommage d’une humanité irrésistible"

ClassiqueNews

”

"Refugiémonos en estas dos horas de paz y esperanza mientras afuera el mundo vuelve a resplandecer y regresa a su causa."

Apocrifa Art Magazine

”

"The renowned early music interpreter is joined by a large ensemble of guest performers for a ‘musical memoir’ that explores the history of slavery in the New World. "

Sight Lines – Joshua Figueroa

”

"Making this a Recording of the Month seems too small an honour. "

Simon Thompson, MusicWeb International (Recording of the month)

Share