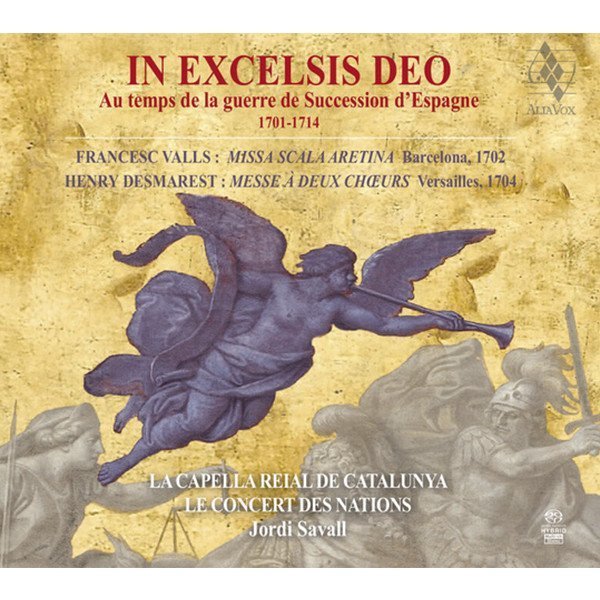

IN EXCELSIS DEO

Au temps de la guerre de Succession d’Espagne

Jordi Savall, La Capella Reial de Catalunya, Le Concert des Nations

21,99€

A, two Masses, Missa “Scala Aretina” à quatre chœurs by the Catalan composer Francesc Valls (1671-1747) and Messe à deux chœurs et deux orchestres by the French composer Henry Desmarest (1661-1741), are presented side by side: two exceptional master-pieces which are linked in time and by the history of the nascent 18th century, but which are less well known than they deserve to be by today’s 21st century audiences.

Reseña Melómano Digital (ESP)

Revue de Res Musica (FRA)

Ressenya de Sonograma (CAT)

Church music, court music and the historical memory of folk songs.

1702-1714

IN EXCELSIS DEO

In this programme “IN EXCELSIS DEO” in the Time of the War of the Spanish Succession, two Masses, Missa “Scala Aretina” à quatre chœurs by the Catalan composer Francesc Valls (1671-1747) and Messe à deux chœurs et deux orchestres by the French composer Henry Desmarest (1661-1741), are presented side by side: two exceptional master-pieces which are linked in time and by the history of the nascent 18th century, but which are less well known than they deserve to be by today’s 21st century audiences. Indeed, these rare works, created by two of the greatest composers of Catalonia and France (they belong to the same generation, Valls being ten years Desmarest’s junior), are linked by the history of conflict between the French and Spanish crowns during the War of the Spanish Succession which began in 1701.Valls’s Missa Scala Aretina,composed in Barcelona at the end of 1701, was performed at the beginning of 1702, whilst Desmarest’s Mass was composed around 1704, just after his stay in Barcelona. The Missa Scala Aretina was performed for the first time at Barcelona Cathedral, whilst the Mass à deux chœurs was probably first performed at the Royal Chapel of Versailles (certainly after 1704, bearing in mind Philidor’s list of musicians taking part in the performance, in which he mentions the names of singers of the royal chapel and court instrumentalists). It was at the height of the terrible war between pro-Bourbon and pro-Habsburg factions in Spain and Catalonia, in which the Spanish and French troops supporting Philip V were pitted against the Catalan and Austrian troops of Archduke Charles of Austria, who were supported by the people of Catalonia in a bid to retain their freedom.

+ information in the CD booklet

JORDI SAVALL

Utrecht, 30th August, 2017

Translated by Jacqueline Minett

Revue par Res Musica

Share