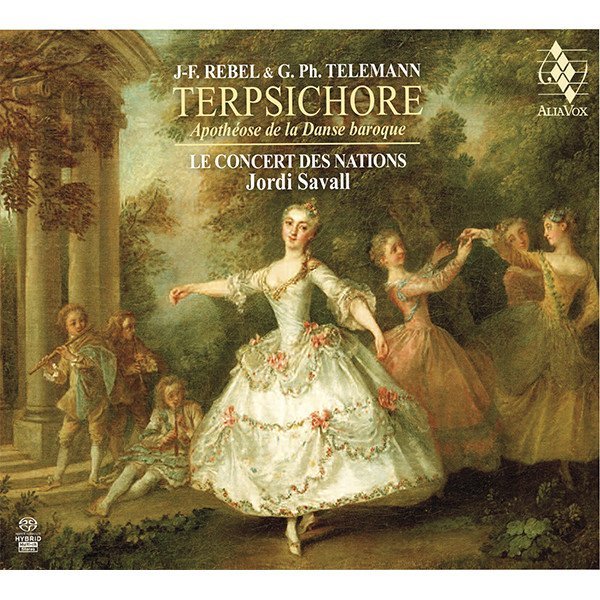

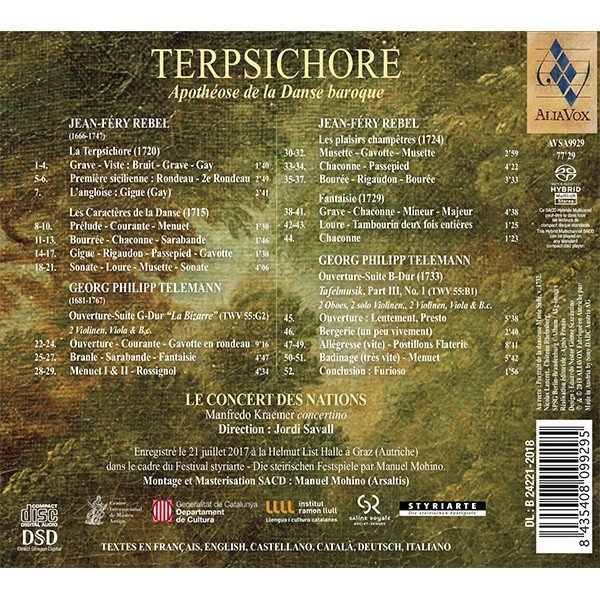

TERPSICHORE

J-F.Rebel & G.Ph.Telemann

Hespèrion XXI, Le Concert des Nations

17,99€

“Dance is the mother of the arts. Music and poetry exist in time, painting and architecture in space. But the dance lives at once in time and space. Rhythmical patterns of time and the organization of space are things that man created by means of the dance in his own body before he used stone and the word to give expression to his emotions.”

Curt Sachs, Introduction to World History of Dance, 1938

TERPSICHORE

Apotheosis of Baroque Dance

Or the Art of Belle Danse

“Dance is the mother of the arts. Music and poetry exist in time, painting and architecture in space. But the dance lives at once in time and space. Rhythmical patterns of time and the organization of space are things that man created by means of the dance in his own body before he used stone and the word to give expression to his emotions.”

Curt Sachs, Introduction to World History of Dance, 1938

Long before it became an essential form of human corporal expression, dance had already been present in most organized societies from the dawn of the history of mankind. The earliest traces depicting the execution of dances are to be found in prehistoric times, in the Palaeolithic, when the existence of primitive dances was recorded in cave paintings.

In the majority of cultures in prehistoric times, dance was above all a feature of ceremonies and rites, often addressed to a higher being and acted as a channel of communication with the ancient Egyptian, Greek and Roman gods. In conjunction with chants and music, it probably also enabled participants to enter into a state of trance, whose various purposes included warding off ill fortune, summoning courage before battle or the hunt, or as a cure for the bite of a venomous snake (the “tarantella”, for example, was used to remedy the effects of the terrible sting of the tarantula spider).

+ information in the CD booklet

JORDI SAVALL

Lisbon, 24th September 2018

Translated by Jacqueline Minett

Critics

”

"Le maestro sait faire chanter, nuances, accents, phrasés à l’envi, son cher orchestre. Superlatif. "

Alain Huc de Vaubert, RES MUSICA

”

"Avec son Concert des nations, Jordi Savall nous révèle avec grande intelligence, noblesse et élégance les subtilités chorégraphiques de ces suites. Là où l’on pourrait considérer la musique du prolifique Telemann convenue, se déroulant au kilomètre comme dans certaines interprétations, il fait chanter avec délectation les nuances, les accents et les phrasés. Un bonheur total, d’autant plus que la qualité de la prise de son et le soin éditorial sont remarquables. "

Alain Huc de Vaubert, RES MUSICA

Share