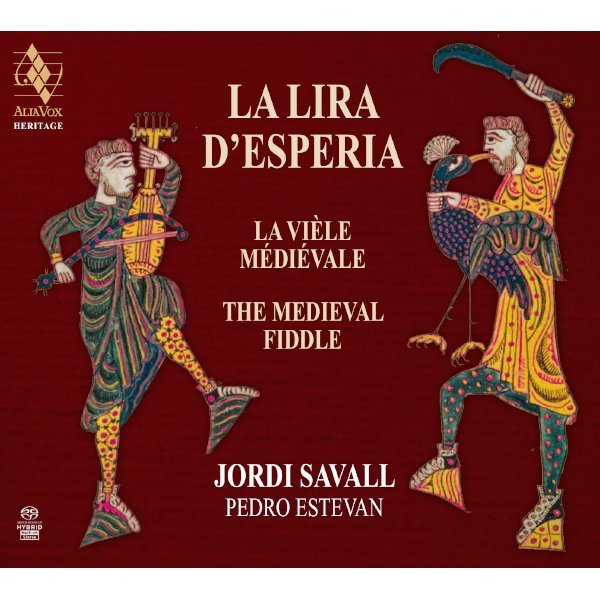

LA LIRA D’ESPERIA

La vièle mèdièvale

Jordi Savall

Alia Vox Heritage

15,99€

The fiddle with its sweet melodies,

sometimes dreamy, sometimes joyful,

sweet notes, delightful, clear, well turned.

The listeners rejoice and make merry.

Arcipreste de Hita, ca. 1330

ALIA VOX AVSA9942

Heritage

CD : 54’54

LA LIRA D’ESPERIA

La Vièle Médiévale

The Medieval Fiddle

CD

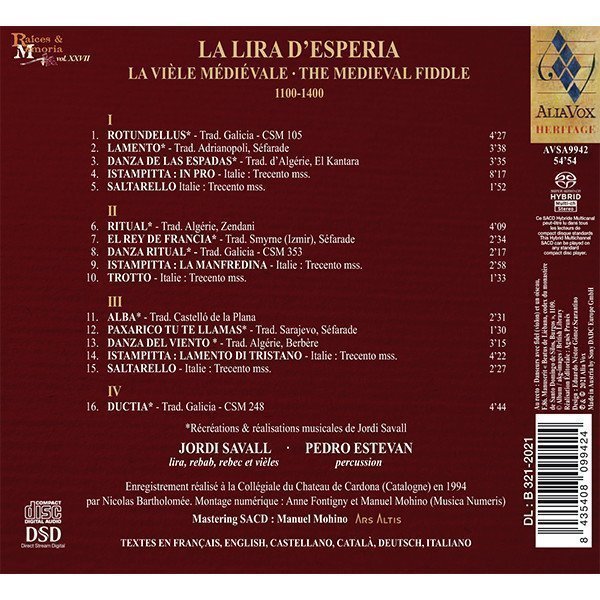

I

- 1.ROTUNDELLUS* – Trad. Galicia – CSM 105

- 2.LAMENTO* – Trad. Adrianopoli, Séfarade

- 3.DANZA DE LAS ESPADAS* – Trad. d’Algérie, El Kantara

- 4.ISTAMPITTA : IN PRO – Italie : Trecento mss.

- 5.SALTARELLO Italie : Trecento mss.

II

- 6. RITUAL* – Trad. Algérie, Zendani

- 7. EL REY DE FRANCIA* – Trad. Smyrne (Izmir), Séfarade

- 8. DANZA RITUAL* – Trad. Galicia – CSM 353

- 9. ISTAMPITTA : LA MANFREDINA – Italie : Trecento mss.

- 10. TROTTO – Italie : Trecento mss.

III

- 11. ALBA* – Trad. Castelló de la Plana

- 12. PAXARICO TU TE LLAMAS* – Trad. Sarajevo, Séfarade

- 13. DANZA DEL VIENTO * – Trad. Algérie, Berbère

- 14. ISTAMPITTA : LAMENTO DI TRISTANO – Italie : Trecento mss.

- 15. SALTARELLO – Italie : Trecento mss.

IV

- 16. DUCTIA* – Trad. Galicia – CSM 248

*Récréations & réalisations musicales de Jordi Savall

JORDI SAVALL

PEDRO ESTEVAN

Enregistrement réalisé à la Collégiale du Chateau de Cardona (Catalogne) en 1994

par Nicolas Bartholomée. Montage numérique : Anne Fontigny et Manuel Mohino (Musica Numéris)

Mastering SACD : Manuel Mohino (Ars Altis).

The Lyra of Hesperia

1100-1400

The earliest string instruments described in Greek mythology, the lyra and the kithara[1] are among those most frequently cited by the Roman poet Virgil (70-19 B.C.). According to Greco-Latin tradition, Apollo invented the lyre, while Orpheus invented the kithara.

From ancient times, there have been constant references to the extraordinary power and effects that music and musical instruments have over people, animals and even plants and trees. Such were the characteristic attributes of Orpheus, whose magical gifts as a musician inspired one of the most mysterious and symbolic myths in Greek mythology. With its origins lost in the mists of time, this myth gradually took on theological proportions, giving rise to a vast and often esoteric body of literature. Orpheus is the musician par excellence, whose enchanting melodies charmed wild beasts, caused trees and plants to bend down before him and soothed even the fiercest of men.

Hesperia (Esperia in Italian) was the name given in Antiquity to the two most westerly peninsulas, the Italian and the Iberian. According to the Greek philosopher Diodorus, this was also the location of the Hesperides, or Atlantis, a wondrous garden where the magical Golden Apples (…oranges or lemons?) were to be found.

+ information in the CD booklet

JORDI SAVALL

Bellaterra, autumn 1995

Translated by Jacqueline Minett

[1] The lyra originally had a sound box made from a tortoiseshell and was used for musical education and amateur enjoyment. The kithara was the instrument of professionals and was used in musical contests, public festivals etc.; its sound box was constructed from wood.

[2] Members of a class of lyric poets, living in southern France, eastern Spain and northern Italy from 11th-13th c., who sang in Provençal (Langue d’oc) chiefly of chivalry and gallantry; sometimes including wandering minstrels and jongleurs. (O.E.D.)

[3] Medieval itinerant minstrels, who sang, played an instrument and composed ballads, told stories and otherwise entertained people ‘

[4] French music theorist who was flourishing round about 1300.

[5] Grocheio divided musica vulgaris (in the vernacular) into two categories, cantus and cantilena. Each of these was then given a triple subdivision. The three forms of the cantus were cantus gestualis, cantus coronatus and cantus versiculatus (or cantus versualis). Cantus gestualis obviously meant chanson de geste, but the distinction between the other two is not at all clear. The term cantilena was applied to the secular refrain forms that Grocheio identified with the music of the people of northern France – hence the three subdivisions: rotundellus (rondeau), and (without text) stantipes (estampie) and ductia. The ductia was a textless instrumental composition with a regular beat – e.g. the pieces entitled danse in the Manusctit du Roi. (For all these subjects, see articles by H. Vanderwerf and E.H. Sanders in the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians.)

Share