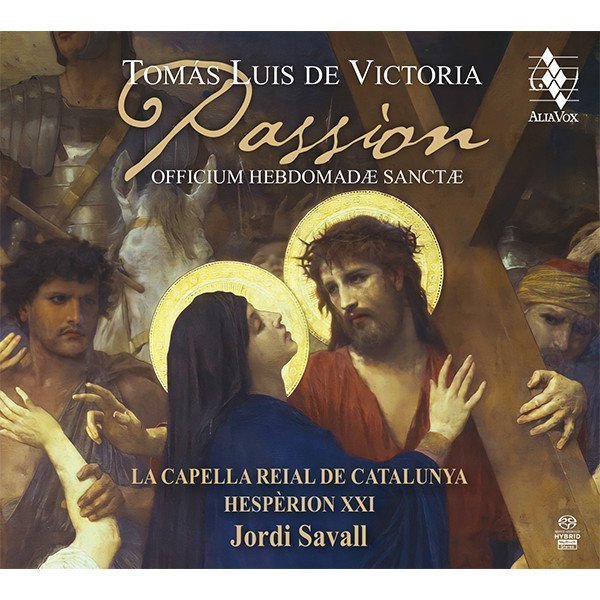

TOMÁS LUIS DE VICTORIA · Passion

Officium Hebdomadæ Sanctæ

Hespèrion XXI, Jordi Savall, La Capella Reial de Catalunya

34,99€

Tomás Luis de Victoria’s OFFICIUM HEBDOMADÆ SANCTÆ is one of the most compelling examples of creative genius in a composer, a toweringly poignant and masterpiece on the Passion of Christ, a pure but infinitely subtle creation, Ad majorem Dei gloriam.

ALIA VOX

AVSA9943

CD1 : 75’44

CD2 : 68’07

CD3 : 58’89

TOMÁS LUIS DE VICTORIA

OFFICIUM HEBDOMADÆ SANCTÆ

LIVE RECORDING

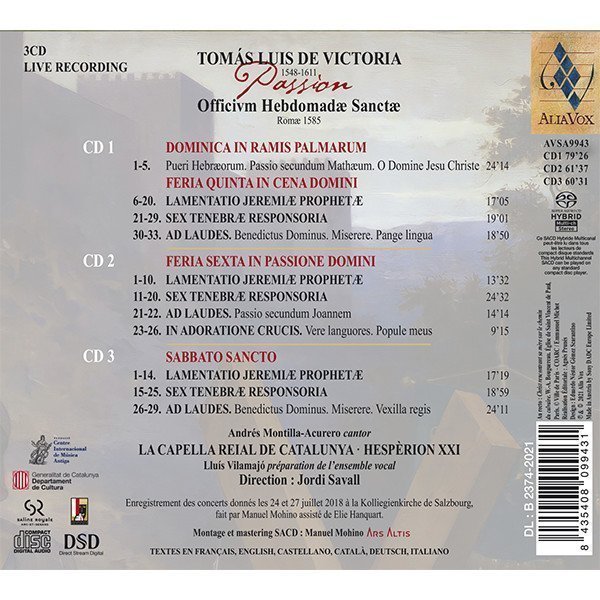

CD1

DOMINICA IN RAMIS PALMARUM

1-5. –Pueri Hebræorum. Passio secundum Mathæum. O Domine Jesu Christe

FERIA QUINTA IN CENA DOMINI

6-20. – LAMENTATIO JEREMIÆ PROPHETÆ

Lectio Prima, Lectio Secunda, Lectio Tertia

21-29. SEX TENEBRÆ RESPONSORIA

30-33. AD LAUDES. Benedictus Dominus. Miserere. Pange lingua

CD2

FERIA SEXTA IN PASSIONE DOMINI

1-10. LAMENTATIO JEREMIÆ PROPHETÆ

11-20. SEX TENEBRÆ RESPONSORIA

21-22. AD LAUDES. Passio secundum Joannem

23-26. IN ADORATIONE CRUCIS. Vere languores. Popule meus

CD3

SABBATO SANCTO

1-14. LAMENTATIO JEREMIÆ PROPHETÆ

15-25. SEX TENEBRÆ RESPONSORIA

26-29. AD LAUDES. Benedictus Dominus. Miserere. Vexilla regis

Andrés Montilla-Acurero – Cantor

LA CAPELLA REIAL DE CATALUNYA

Lluís Vilamajó préparation de l’ensemble vocal

Direction : JORDI SAVALL

Enregistrement des concerts donnés les 24 et 27 juillet 2018 à la Kolliegienkirche de Salzbourg

Enregistrement, Montage et Mastering SACD : Manuel Mohino (Ars Altis)

TOMAS LUIS DE VICTORIA

OFFICIUM HEBDOMADÆ SANCTÆ

Mysticism and Passion: an absolute masterpiece

More than 70 years ago, the sequences of Gregorian chant and polyphonic music such as that of Tomás Luis de Victoria made a profound impression on my musical experience at that time from 1949 to 1953, when I was a chorister under the direction of Joan Just in the boys’ choir of the Piarist school at Igualada, Catalonia. To have been submerged in the beauty of that music during my childhood unquestionably made a lasting impact and shaped certain aspects of my education as a chorister, and particularly my musical sensibility. The memory of those spellbinding chants also had a decisive influence on my choice to study the cello a few years later, just before I turned 15, when I was spellbound one evening at a rehearsal of Mozart’s Requiem. It was after that evening of extraordinary intensity, and thanks to Joan Just, who conducted the choir of the Schola Cantorum in Igualada, that I fully realized the power of music and decided to become a musician.

There followed years of study at the Barcelona Conservatoire (diploma in violoncello in 1964), then my discovery of the viola da gamba (1965), specialist studies and periods of research in the ancient libraries of Europe and the New World, my years of study in Basel (1968-70) and teaching at the SCHOLA CANTORUM BASILIENSIS (1973-93), followed by the founding of various ensembles: HESPÈRION XX (1974), LA CAPELLA REIAL (1987) and LE CONCERT DES NATIONS (1989), with which we made numerous concert tours and recordings, and finally the creation of the record label ALIA VOX (1998). All of this led to our wide-ranging familiarity with repertories in the world of early music, and, as is the case of the Victoria recording that we present here, a moving return to my deepest roots.

+ information in the CD booklet

Jordi Savall

Bellaterra, 3 March, 2021

Translated by Jacqueline Minett

Critics

”

”

Viele nicht in der Partitur notierte Instrumente spielen mit, der Klang ist warm, dunkel, meditativ, ein leichter Zug verbindet die Nummern zu einem großen Ganzen, das keinerlei Exzesse kennt, nie Virtuosität ausstellt, aber immer Sinn, Gnade, Versöhnung und reine Schönheit atmet: atemloses Staunen.

Süddeutsche Zeitung. Reinhard J. Brembeck. 21. Juni 2021 |

”

“Es uno de los ejemplos más rotundos del genio creador de un compositor que logra una inmensa y desgarradora obra maestra mística sobre la Pasión de Jesucristo, creada puramente, pero con una sutileza infinita” concluye el maestro Jordi Savall

Los Sonidos del Planeta Azul, 21/04/22

Share